NOAA Creates Workarounds for Malfunctioning Weather Satellite

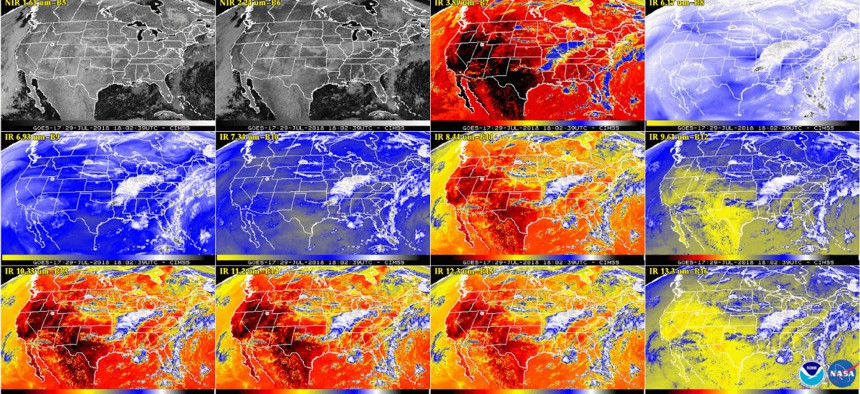

This multiple panel image shows a snapshot of the continental U.S. and surrounding oceans from some of the Advanced Baseline Imager channels at 2:02 p.m. EDT on July 29, 2018. NOAA/NASA

The GOES-17 still isn’t working the way it’s meant to, but engineers believe they have a way to make it more functional than not.

Federal officials still aren’t sure why the cooling system on one of the government’s newest weather satellites isn’t working, but engineers have been able to increase the imaging capability significantly since the issue first arose.

The newest Geostationary Operational Environmental constellation satellite, dubbed GOES-17, launched on March 1 and went into a six-month check-out period before joining the constellation. During that time, engineers discovered a problem: The cooling system for the satellite’s main camera—the Advanced Baseline Imager—wasn’t functioning properly.

The camera was designed to record images across 16 spectra of light, from the visible to the invisible. However, the cooling malfunction means the majority of those bands—the 13 infrared bands—were unusable half the time. Due to the satellite’s projected geostationary orbit over the western United States, the camera’s lens points directly at the sun during nighttime hours, overheating the system for about 12 hours a day.

Wednesday, officials from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said that while the team has yet to identify the cause of the problem, it was able to make adjustments to get more functionality than first expected. The agency also released the first pictures from the compromised spectral bands.

During the “cool seasons”—the periods closest to the summer and winter solstice—NOAA engineers say the imager will be fully functional and be able to take pictures across all 16 bands, 24 hours a day. And while the warm seasons—near the vernal and autumnal equinox—will still pose a problem, engineers said only nine bands will be unusable, and then only for two to six hours each night.

With the autumnal equinox approaching, the engineers will get to test that theory before the end of the year.

Despite not having full functionality, NOAA officials say GOES-17 still adds to the overall imaging power of the constellation and will be moved into an operational configuration with the other satellites before the end of the year. A team from NOAA’s Office of Satellite and Product Operations, the National Weather Service and other relevant stakeholders will help determine exactly how the satellites will be positioned, given GOES-17’s degraded service.

During a July call with reporters, Joe Pica, director of NWS’ Office of Observations, said he had “confidence in the team that we’ll come up with a solution that makes GOES-17 a significant and valuable contribution to our capabilities.”

However, officials also said the launch of the next two planned GOES satellites—scheduled for 2020 and 2024—could be postponed if engineers still aren’t able to identify the problem with the cooling system.

The GOES constellation is being heralded as a significant step forward in NOAA’s ability to track weather systems, as well as an answer to an impending gap in satellite coverage. Progress on the GOES program prompted the Government Accountability Office to remove the geostationary gap from its biennial high-risk list in 2017. GAO researchers have asked for a briefing on the latest developments.

NEXT STORY: America Is Not Ready for Exploding Drones