How a Library Embraced New Technology and Helped Build a Prosthetic Hand

stockddvideo/Shutterstock.com

The public library in a small Texas town used an assessment tool that helped officials eventually upgrade equipment—including buying a 3D printer. One community member used it to make a prosthesis.

Four years ago, occupational therapist Adrian Vega crafted a custom prosthetic for a 6-month-old infant born with just one hand.

He made it at the local library, using a 3D printer.

"He called me," recalled Mendell Morgan, director of the El Progreso Memorial Library in Uvalde, a southern Texas town with a population of around 16,000. "And said, 'Mr. Morgan, I read in the paper that you've got a new 3D printer.' And I said, 'Yes,' all perked up, and he said, 'May I come over and make a hand for a client of mine who's 6 months old?'

"And I said, 'You want to do what now?'"

The library had just acquired the printer as part of a new suite of equipment purchased through a technology grant that officials had applied for after completing an assessment through Edge, a performance indicator system. That test had identified gaps in the facility’s technology that could be partially addressed by equipment upgrades.

“Edge gives a framework of questions, standards, benchmarks you might be wanting to attain, and when you’re thinking about those questions you’re having to assess where you stand. It’s an evaluative tool,” Morgan said. “Depending on the results, it helps you formulate the strategies you need to employ.”

Edge, created by a national coalition and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is overseen by the Urban Libraries Council, which launched an updated version of the platform this month. The system allows library officials to assess their services against the needs of their communities.

The upgrade features updated benchmarks and gives users the ability to compare their facilities to libraries of similar sizes and to save and manage action plans online. The goal is to help libraries showcase their successes and target areas for improvement, which can help secure funding from both local governments and outside organizations.

“If they’re able to say, ‘Hey, our library is underperforming on serving disabled members in our community, and I can show with Edge that we’re lagging behind other similarly sized communities,’ that’s shown to be a very effective tool for libraries to get grants and other tools for improvement,” said Curtis Rogers, director of communications for the Urban Libraries Council.

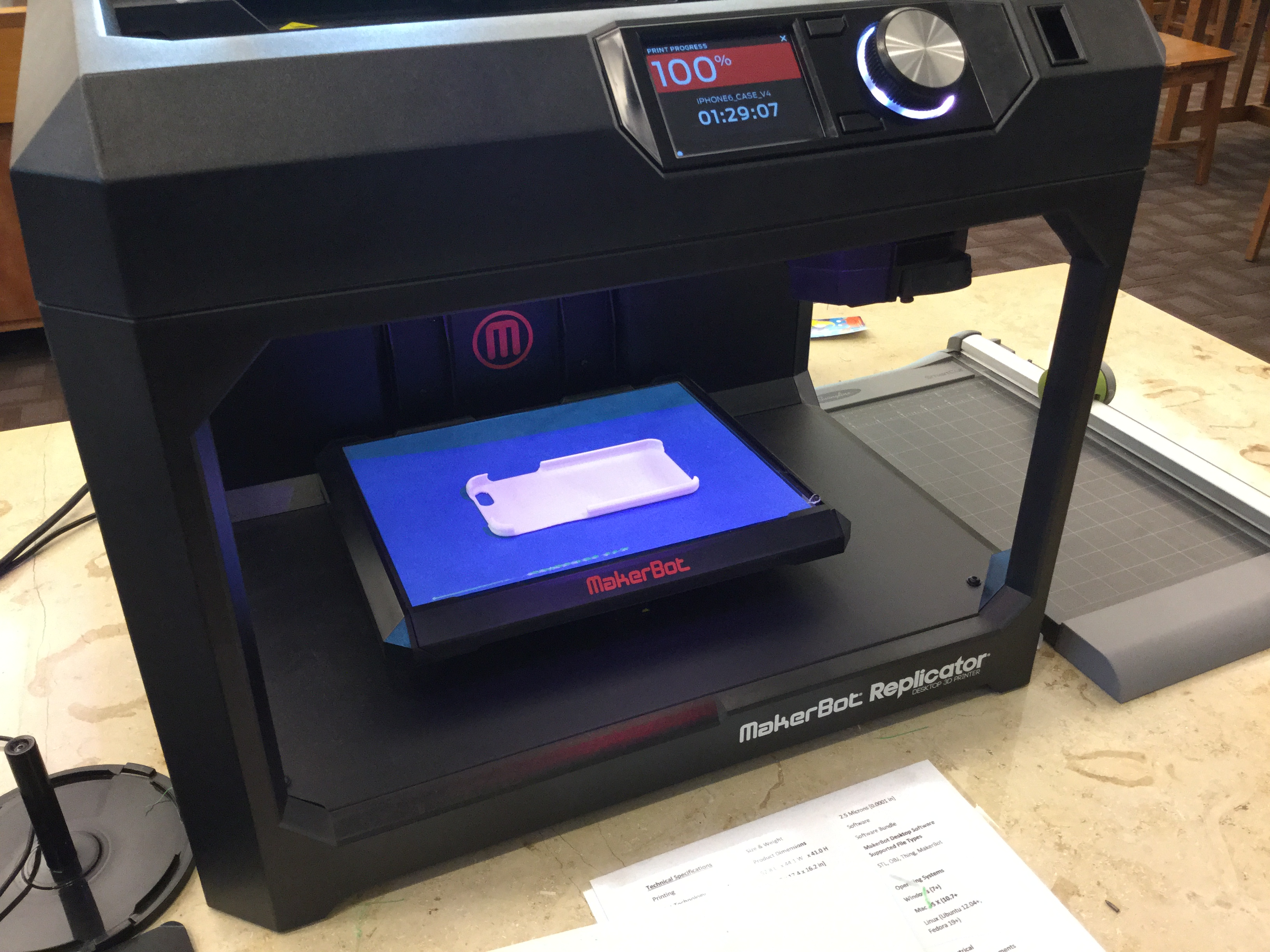

At El Progreso Memorial Library, Morgan did just that, using assessment results to secure a $10,000 technology grant offered by the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Morgan used the money to purchase several computers, four iPads, a poster printer, a high-speed scanner and, notably, a 3D printer—the first of its kind in Uvalde.

“I was aware that other libraries had them, and in going through the process of that assessment it appeared it would be a very good thing because a lot of libraries are going into what they call ‘maker space,’” Morgan said. “It wasn’t offered in the community elsewhere. Even though we’re somewhat isolated and rural, I wanted our users to feel like they had the amenities like a big-city library would have.”

Morgan pictured community members using the printer to make cell-phone cases, bracelets, replacement buttons and Christmas decorations—all “nice applications,” he said. But shortly after the device was installed, Vega called with an entirely different kind of project in mind.

Vega’s client, 6-month-old Elijah, was afflicted with amniotic band syndrome, which occurs before birth when a fetus becomes entangled in fibrous, string-like bands of amniotic fluid in the womb. In Elijah’s case, the band wrapped entirely around his arm, impeding the development of one hand. Vega told Morgan that he had previously used a 3D printer to create a hand facsimile for an adult, and was interested in doing the same thing for Elijah.

“I said, ‘Please come over here right now and show me,’” Morgan said.

Vega came to the library with a thumb drive that loaded a printer program onto the computer. The printer constructed the hand in stages—first the lower parts of the fingers, then the upper half—which Vega then took home to assemble.

“Eventually he put it on the little boy, who was thrilled because he could immediately get anyone’s attention by smacking them with his plastic hand,” Morgan said.

Vega returns to the library periodically to print new devices that keep pace with Elijah's size as he grows older. The project brought publicity to the library and helped Morgan demonstrate the facility’s importance, a constant struggle in Uvalde, where only about half of the library’s budget is funded by local municipalities.

“It costs, realistically, about $465,000 per year to run the place. The city is presently giving us $102,000 and the county about $127,000,” Morgan said. “We’re always on the lookout for things we can do to raise money, and Edge helps with that by giving me ideas about how technology can be embraced.”