Government Needs An ‘Ethical Framework’ to Tackle Emerging Technology

tsyklon/Shutterstock.com

At SXSW, a beacon of technology idealism, mayors discuss how to deal with the difficult problems that can come with new tech.

AUSTIN, Tex.—It is practically unheard of for a company to urge the government to regulate them. But that’s what Microsoft did last July when Bill Smith, the company’s president and chief legal officer, penned a piece urging governments to step in and impose some rules on facial recognition technology.

“Even a broom can be used to sweep the floor or hit someone over the head,” he wrote. “The more powerful the tool, the greater the benefit or damage it can cause.”

While Silicon Valley has been generally focused on the ideals of technology to save society, it has become readily apparent that rapid innovation has unintended consequences. On Friday in Austin, Texas, a cadre of mayors delved into these issues, and the effects on their citizens and governments.

Facial recognition was only a small area of discussion. Katie Joseff, an expert on emerging technologies’ impact on society with the Institute for the Future, walked the mayors through numerous issues that are arising as technology becomes more intelligent and omnipresent. Algorithms promising to predict child abuse have unintentionally targeted poor families, she noted, while smart home technology is being exploited by domestic abusers to harass and control victims. Emerging artificial intelligence can produce “deepfakes,” video and audio that show individuals doing something they have never done, opening new worlds of misinformation.

To display the last point, the team from the Institute for the Future put together a stream of fake videos, from Austin Mayor Steve Adler sitting down with Vladimir Putin to West Sacramento Mayor Christopher Cabaldon replacing Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson in a movie. The results weren’t perfect, but the team pointed out that these deepfakes are increasingly realistic as the artificial intelligence that fuels them continues to get better.

Joseff and colleagues have built a toolkit called EthicalOS, a framework through which “policymakers, funders, product managers, engineers and others can get out in front of problems before they happen.”

“As mayors, it’s especially important for you to be aware of these ethical frameworks because you can make an immediate difference in the regulatory structures to protect these really important public goods like truth, privacy, democracy and humanities well-being,” Joseff said.

The toolkit has three parts, aimed in total at thinking broadly about technology and the future, identifying current concerns and ultimately “embedding” what they learn into future policies and actions.

To help the mayors think broadly about technology, the team posited futures scenarios that help people think creatively about potential consequences. Joseff asked the mayors to consider neurotech implants that could help provide “near-to-perfect” recall on memories for individuals. This technology, she pointed out, was not completely the realm of science fiction, citing a University of Southern California project funded by DARPA that built an implant that could improve short-term memory by up to 30 percent.

Mayors traded questions about the implications—ranging from who else might have access to an individual’s thoughts to the possibility of intercepting thoughts of criminal intent. And, yes, the movie “Minority Report” was mentioned.

“My biggest concern on this is memories aren’t like a television,” Nan Whaley, mayor of Dayton, Ohio said. “You remember things the way you want to remember them.” Others pointed to the need to forget playing a role in reducing post-traumatic stress.

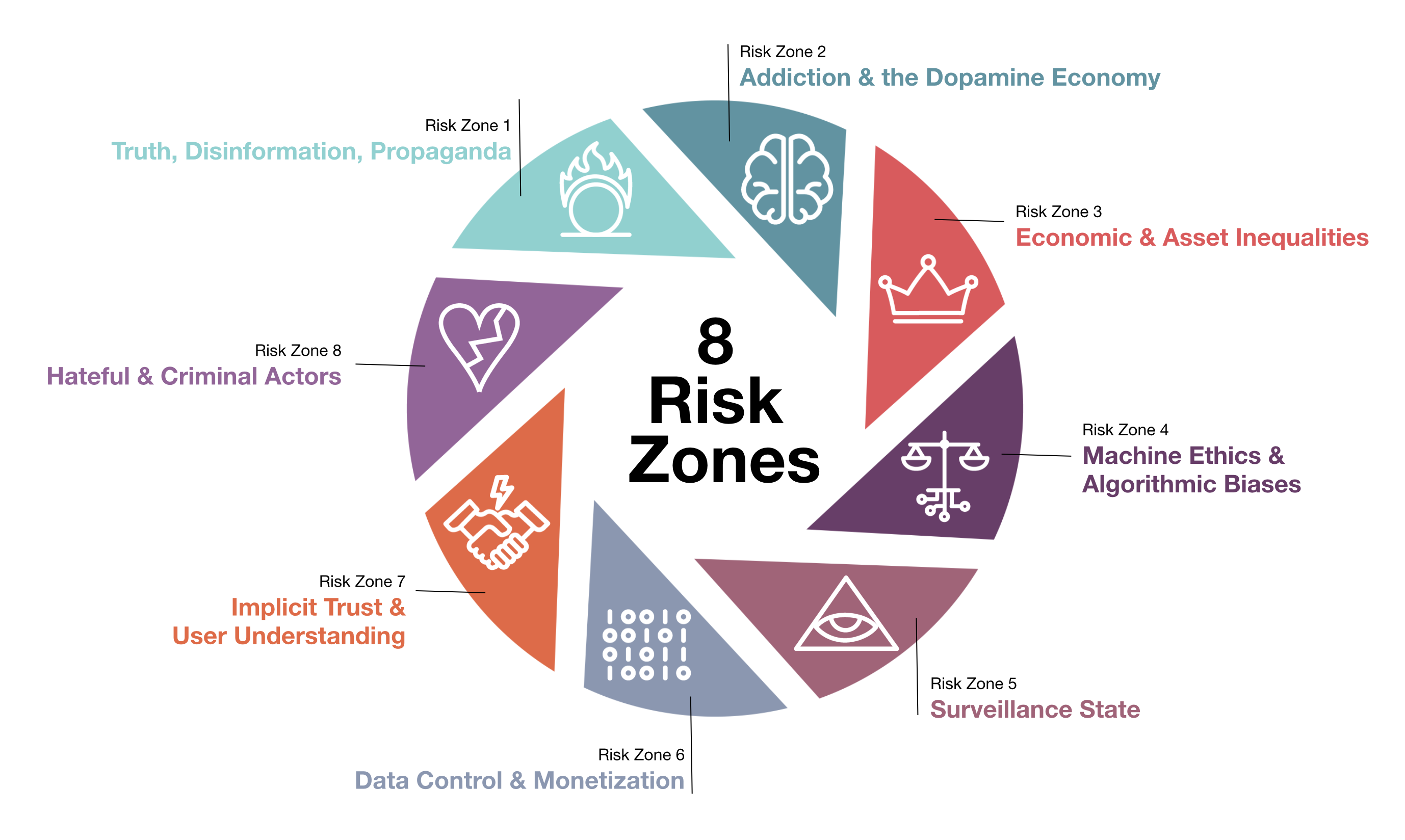

Mayors were also given eight “risk zones” based on hard to mitigate concerns for existing technologies, such as addiction to the technology, use by hateful or criminal actors, increasing ease of surveillance and exacerbating inequities.

Standards around surveillance technology and body cameras were a particularly present and real topic for the mayors. Adrian Perkins, the recently elected mayor of Shreveport, Louisiana pointed to a proposal to place new cameras and surveillance technologies in his city’s downtown to reduce crime. When first proposed by the downtown development authority, procedures were not in place to protect privacy or deal with the security concerns inherent in filming individuals in public areas, he said. Perkins’ new chief technology officer is now working with the authority to implement governance rules.

“They were way out in front,” Perkins said. “Right now we are looking at how we can roll it out in a responsible way… protecting the citizens.”

The hope is with these two tools, mayors can take a third step of building “future-proofing” policies and strategies that help mitigate some of the potential dangers of new technologies.

But as some of the mayors pointed out, perhaps some of the problems were not the technologies, but us.

“[You are] describing it as future-proofing, as if the present and the past is just fine,” West Sacramento Mayor Christopher Cabaldon said, providing an example of biased algorithms as a product of the people creating them. “I know in my city we have a tendency to really obsess about the consequences of new things, but some of these new things are just making visible the problems with the old things.”

NEXT STORY: On the Brink of a New Era of Spaceflight