30 Years Later, NOAA Administrator Reflects on Her Spacewalk

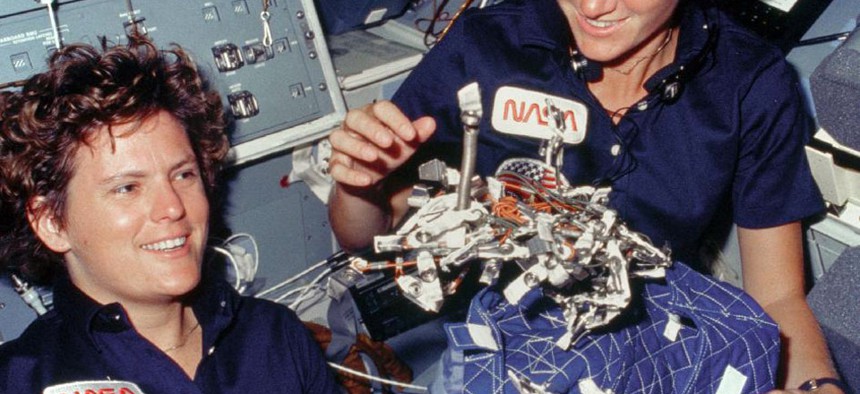

Astronauts Kathryn D. Sullivan, left, and Sally K. Ride display a "bag of worms" during the STS-41G mission in 1984. The bag is a sleep restraint and the majority of the 'worms' are mostly springs and clips used with the sleep restraint. NASA

The first American woman to walk in space shares her experience, three decades later.

Almost 30 years ago, Kathryn Sullivan – now the administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – became the first American woman to walk in space as a crew member of the space shuttle Challenger.

Sullivan was among six women who comprised NASA’s first class of female astronauts and is widely recognized as a trailblazer for women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields. Millions watched Sullivan stroll around several hundred miles above the Earth’s surface on Oct. 11, 1984. And those who didn’t see the event didn’t have to look far to read about it.

“The picture and story were on the same page as [vice presidential candidate] Geraldine [Ferraro] in The New York Times,” Sullivan said Wednesday at an event hosted by Pew Charitable Trusts. “Front page, above the fold.”

As the first female vice presidential candidate, Ferraro’s debate that same day with then-Vice President George H.W. Bush was perhaps an equally momentous occasion. Yet Sullivan’s efforts were not the pinnacle of her achievements, but rather a glimpse of what was to come for the esteemed scientist.

The first American woman to walk in space went on to document Earth’s oceans before her current dual role as NOAA administrator and undersecretary of commerce for oceans and atmosphere – titles that led to TIME magazine dubbing her “The World’s Weatherwoman.”

In her NOAA role, Sullivan oversees programs, satellites and instruments that essentially take the Earth’s pulse each day. All told, they produce 20 terabytes of data per day – twice the printed volume of the Library of Congress – that feed into global weather forecasts and an assortment of other measurements.

“It was pretty crazy back then,” Sullivan said, reflecting on her days as one of NASA’s first female astronauts. “NASA had not welcomed astronauts for nine years – NASA was figuring this out as well. And I don’t think NASA even realized what the reaction was going to be.”

It was, she said, an on-the-job education. Prior to Sullivan, the only female anything NASA launched in space were two spiders and a monkey, so NASA’s astronaut facilities weren’t exactly equipped for women. As least, not human women.

Among the interesting tidbits Sullivan shared Wednesday:

- Initially, ground spaceflight facilities where astronauts trained didn’t have female locker rooms. Sullivan credits Carolyn Huntoon, who later went on to serve as the Johnson Space Center director, for handling several gender-related issues that sprang up for NASA’s first class of female astronauts. Huntoon was an integral mentor to the astronauts.

- Apparently, Sullivan said, some NASA officials wondered about a dress code for the new female astronauts. Huntoon, she said, again stepped in. If the astronaut men didn’t have a dress code, then the female astronauts wouldn’t, either.

That Sullivan’s story – overcoming gender barriers and busting down the good old boys’ club door – still resonates today indicates larger problems within the tech- and science-heavy sides of government.

Recent statistics reported by Nextgov showed that women hold just 31 percent of information technology positions across government. Even fewer women – about 28 percent – occupy physical science positions, according to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. And only 15 percent of the government’s engineering and architecture positions are held by women.

Problems are compounded by the fact that tech and science workplaces apparently don’t do much to attract or retain female talent. Statistics in a 2014 multinational report by the Center for Talent Innovation suggest women are fleeing science and tech fields in droves. It’s still big news when a woman such as former Google executive Megan Smith fills a high-ranking tech or science position – not because of her tech chops or acumen, but because she’s a she.

Still, Sullivan’s efforts illuminate a path that, while less traveled, has been astoundingly rewarding to her.

“These women carried the hopes and dreams of millions who saw their bold journeys as their own tickets to success,” said Lynn Sherr, a journalist who has followed America’s space program for several decades. Sherr spoke about Sullivan and the original class of female NASA astronauts at the Pew event.

“Kathy’s great accomplishment is not only that she helped shatter that glass ceiling, but that she did it so magnificently,” Sherr said. “She continues to serve people and the planet.”