Why Improvisation Is the Future in an AI-Dominated World

Olemedia/istockphoto.com

Which human activities will survive the rise of intelligent machines?

In his autobiography, Miles Davis complained that classical musicians were like robots.

He spoke from experience – he’d studied classical music at Juilliard and recorded with classical musicians even after becoming a world-renowned jazz artist.

As a music professor at the University of Florida, which is transforming itself into an “AI university,” I often think about Davis’ words, and the ways in which musicians have become more machinelike over the past century. At the same time, I see how machines have been getting better at mimicking human improvisation, in all aspects of life.

I wonder what the limits of machine improvisation will be, and which human activities will survive the rise of intelligent machines.

The rise of machine improvisation

Machines have long excelled at activities involving consistent reproduction of a fixed object – think identical Toyotas being mass-produced in a factory.

More improvised activities are less rule-based, more fluid, chaotic or reactive, and are more process-oriented. AI has been making significant strides in this area.

Consider the following examples:

The trading pits of Wall Street, Tokyo and London were once filled with the vibrant chaos of traders shouting and signaling orders, reacting in real time to fluidly changing conditions. These trading pits have mostly been replaced by algorithms.

Self-driving technology may soon replace human drivers, automating our fluid decision-making processes. Autonomous vehicles currently stumble where greater mastery of improvisation is required, such as dealing with pedestrians.

Much live social interaction has been replaced by the sterile activity of carefully composing emails or social media posts. Predictive email text will continue to evolve, bringing an increasingly transactional quality to our relationships. (“Hey Siri, email Amanda and congratulate her on her promotion.”)

IBM’s computer Deep Blue defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997, but it took 20 more years for AI to defeat top players of the board game go. That’s because go has a far greater number of possible move choices at any given time, and virtually no specific rules – it requires more improvisation. Yet humans eventually became no match for machine: In 2019, former world go champion Lee Sedol retired from professional play, citing AI’s ascendancy as the reason.

Music becomes more machinelike

Machines are replacing human improvisation at a time when classical music has abandoned it.

Before the 20th century, nearly all of the major figures of Western art music excelled at composition, performance and improvisation. Johann Sebastian Bach was mostly known as an organist, with his first biographer describing his organ improvisations as “more devout, solemn, dignified and sublime” than his compositions.

But the 20th century saw the splintering of the performer-composer-improviser tradition into specialized realms.

Performers faced the rise of recording techniques that flooded consumers with fixed, homogeneous and objectively correct versions of compositions. Classical musicians had to consistently deliver technically flawless live performances to match, sometimes reducing music to a sort of Olympics.

Classical pianist Glenn Gould was both a source and product of this state of affairs – he despised the rigidity and competitiveness of live performance and retired from the stage at the age of 31, but retreated to the studio to painstakingly assemble visionary masterpieces that were impossible to perform in one take.

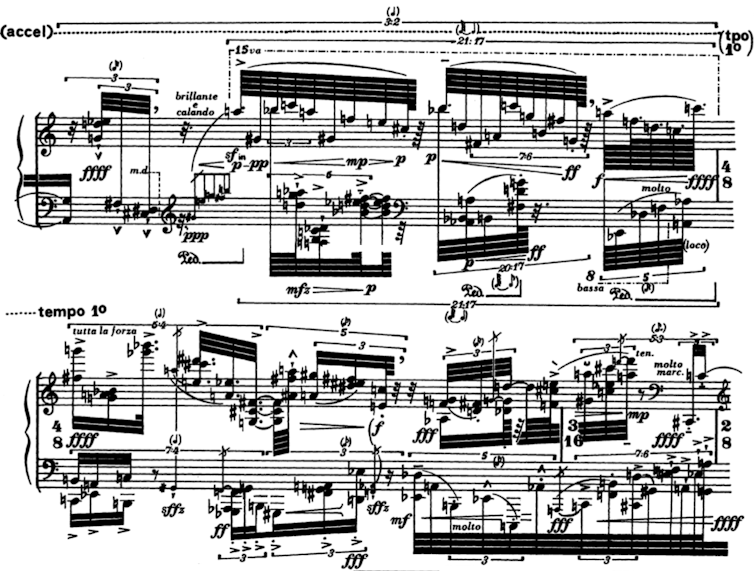

Composers mostly abandoned the serious pursuit of improvisation or performance. Modernists became increasingly enthralled with procedures, algorithms and mathematical models, mirroring contemporary technological developments. The ultra-complex compositions of high modernism required machinelike accuracy from performers, but many postmodern minimalist scores also demanded robotic precision.

Improvisation ceased almost entirely to be a part of classical music, but flourished in a new art form: jazz. Yet jazz struggled to gain parity, particularly in the U.S., its country of origin, due in large part to systemic racism. The classical world even has its own version of the “one-drop rule”: Works containing improvisation or written by jazz composers are often dismissed as illegitimate by the classical establishment.

A recent New York Times article called on orchestras to open themselves up to improvisation and collaborate with jazz luminaries such as saxophonist Roscoe Mitchell, who has composed many orchestral works. But college and university music programs have segregated and marginalized jazz studies, leaving orchestral musicians bereft of training in improvisation. Instead, musicians in an orchestra are seated according to their objectively ranked ability, and their job is to replicate the motions of the principal player.

They are the machines of the music world. In the future, will they be the most disposable?

Davis perfects the art of imperfection

The march of AI continues, but will it ever be able to engage in true improvisation?

Machines easily replicate objects, but improvisation is a process. In pure musical improvisation, there’s no predetermined structure and no objectively correct performance.

And improvisation isn’t merely instantaneous composition; if it were, then AI would collapse the distinction between the two due to its speed of calculation.

Rather, improvisation has an elusive, human quality resulting from the tension between skill and spontaneity. Machines will always be highly skilled, but will they ever be able to stop calculating and switch to an intuitive mode of creation, like a jazz musician going from the practice room to the gig?

Davis reached a point at Juilliard where he had to decide on his future. He connected deeply with classical music and was known to walk around with Stravinsky scores in his pocket. He would later praise composers from Bach to Stockhausen and record jazz interpretations of compositions by Manuel de Falla, Heitor Villa-Lobos and Joaquín Rodrigo.

Yet there were many reasons to abandon the classical world for jazz. Davis recounts playing “about two notes every 90 bars” in the orchestra. This stood in stark contrast to the extraordinary challenge and stimulation of late-night jam sessions with musicians like Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker .

He experienced the reality of racism and “knew that no white symphony orchestra was going to hire [him].” (By contrast, Davis regularly hired white players, like Lee Konitz, Bill Evans and John McLaughlin.)

And he was the antithesis of a machine.

But in jazz, Davis was able to transform his technical struggles with the trumpet into a haunting, iconic sound. His wrong notes, missed notes and cracked notes became wheezes, whispers and sighs expressing the human condition. Not only did he own these “mistakes,” he also actively courted them with a risky approach that prioritized color over line and expression over accuracy.

His was the art of imperfection, and therein lies the paradox of jazz. Davis left Juilliard after three semesters, but became one of the single most important musical figures of the 20th century.

Today the ground has shifted.

Juilliard has a thriving jazz program led by another trumpeter versed in both classical music and jazz – Wynton Marsalis, who has received two classical Grammy awards for his solo work. And while the narrative of “the robots coming for our jobs” is cliché, these displacements are happening quickly, accelerated greatly by the COVID-19 pandemic.

We are hurtling toward a time when actual robots could conceivably replace Davis’ classical “robots” – perhaps some of the 20 violinists in a symphony orchestra – if only at first as a gimmick.

However, we may soon discover that jazz artists are irreplaceable.

Rich Pellegrin is an assistant professor of music theory and affiliate assistant professor in the Center for Arts, Migration, and Entrepreneurship at the University of Florida.

![]() This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.