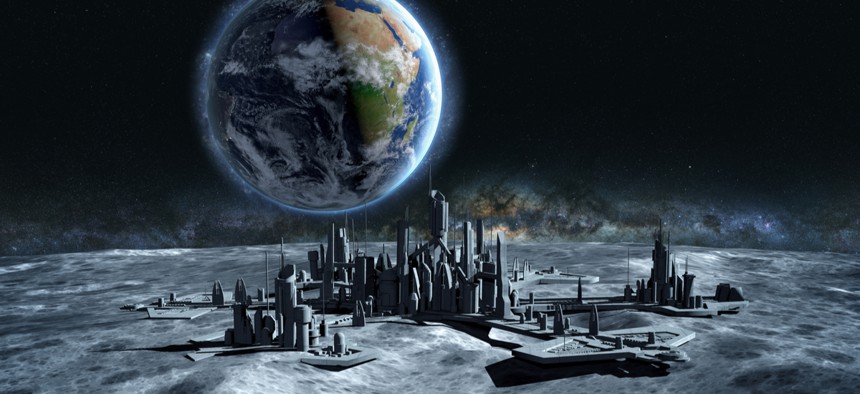

We Were Promised Moon Cities

Pavel Chagochkin/Shutterstock.com

It’s been 50 years since Apollo 11 put humans on the surface of the moon. Why didn’t we stay and build a more permanent lunar base? Lots of reasons.

When Neil Armstrong took his giant leap for mankind on the moon’s surface 50 years ago this week, many people were already dreaming about staying.

Thinkers proposing moon cities ranged from author Arthur C. Clarke, who in 1954 envisioned igloo-shaped buildings on the moon’s surface powered by a nuclear reactor, to the participants in 1968’s Stanford-Ames Summer Faculty Workshop in Engineering Systems Design, who proposed a “Moonlab” that would begin as a three-person observatory before gradually expanding to include 24 people and extensive lunar farms. The pop culture of the Apollo era was full of moon settlements that we could expect by the 1990s: The one in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey boasted 1,100 residents and looked like the minimalist headquarters of a very well-funded interior design company.

But none of this came to pass. The last human set foot on the moon in 1972.

So what happened to the lunar colonies that seemed so imminent 50 years ago?

We’ve Had Other Priorities

Many experts say there was nothing stopping humanity from following the Apollo missions with a permanent settlement. We had the technology to do it. But given the huge expense involved in such an endeavor, humans opted to spend limited resources solving (and, well, creating) problems here on Earth.

“The bottom line why we’re not there is there hasn’t been political will for it,” said Joanne Gabrynowicz, a professor emerita of space law at the University of Mississippi.

James Head, a professor of geological science and planetology at Brown University who worked on the Apollo missions in the 1960s and 70s, recalled the social tumult at the time Americans were walking on the moon.

“I worked on Apollo by day, absolutely ... but I also was almost every weekend down protesting the Vietnam War and witnessing race riots in Washington, D.C.,” Head said.

With all those competing domestic needs for both guns and butter, spaceships just seemed less important, especially once the Cold War reasons of national pride were over. The Apollo program wound down before establishing any sort of permanent presence beyond its “flag-and-footprints” visits, and America’s human spaceflight priorities shifted to low-Earth orbit with Skylab, the shuttle program, and the International Space Station.

A range of experts agreed that technology was never the primary obstacle to establishing a permanent presence on the moon after humans had proven the capability to travel there and back. Instead, it was a cost-benefit analysis that settling the moon didn’t have enough payoff for the cost.

“It’s kind of like asking, ‘Why don’t we have condos in Antarctica?’” said Darby Dyar, a professor of astronomy at Mount Holyoke College who has worked on lunar geology for decades. “We could get stuff there. We have the technology to build structures there. But it would be incredibly expensive to heat them. And why would anyone want to live there?”

Living There’s Actually Really Hard

That’s not to say the technological challenges to lunar living are trivial. Staying on another planet for months or years is far more complex than visiting for a few days. The moon has no atmosphere and is bombarded by heavy doses of radiation and micrometeorites; its surface is covered with surprisingly problematic jagged moon dust and its gravity is one-sixth of that on Earth. Though humans have survived lengthy orbital stays, the effects of extended lunar living on the human body in particular haven’t been researched, especially the low gravity.

“The lunar environment is completely alien to what we experience on Earth,” said Haym Benaroya, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Rutgers University.

Adding to those problems is the enormous expense and difficulty of getting to the moon in the first place. A permanent settlement would require repeated trips to bring supplies and shuttle residents. “Unlike the frequently used Christopher Columbus analogy, or other kind of exploration thing where people say, ‘You brought what you need on your back and you live off the land’—well, you can’t live off the land on the moon,” said Dyar.

There are solutions to all these problems, such as burying settlements under the lunar soil for protection against both radiation and meteors, or mining the frozen water at the lunar poles. And technology has advanced dramatically since the 1970s. Head, the Brown scientist, described one project he worked on that looked at how the Apollo missions could be recreated using modern technology.

“Carbon composites reduce mass significantly. Fuel cell technology has incredibly increased,” Head said. “Space suits are better. We found we could do a fairly inexpensive and very robust mission.”

NASA does have a scheme to return astronauts to the moon by 2024, but it’s expected to cost $20 to $30 billion, and its fate is extremely murky. Overcoming these obstacles still takes a lot of money and attention, which explains why political support for return visits to the moon in past decades has always evaporated.

It’s the Economics, Stupid

But what if lunar settlements could pay for themselves?

“The minute somebody learns how to make money by setting up a base on the moon, there will be a base on the moon,” said Ty Franck, a science fiction author who, with Daniel Abraham, co-wrote the popular The Expanse series of novels, set in a future where humanity has colonized the moon, Mars, and other parts of the solar system.

There are all sorts of ways a lunar settlement could make money. The moon could be mined for raw materials. Solar panels could gather abundant energy, unimpaired by an atmosphere, and beam it back to Earth. Ordinary people could fund a settlement through space tourism. A base on the moon could lower costs for other endeavors, including asteroid mining or trips to Mars.

But none of those are sure bets, which is partly why none of them have been tried.

“Based on the data we have at the present time, we do not have any evidence to say there are economically mineable deposits on the moon,” said Dyar, the specialist in lunar geology.

One possible exception is helium-3, an isotope that could be vital for nuclear fusion. It’s rare on Earth but might be abundant on the moon. Even that is speculative, however.

And the legalities of moon-mining are on very uncertain legal ground. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, to which every spacefaring nation is a party, guarantees the use of space for scientific research, but isn’t clear about commercial uses. Nation-states are forbidden from claiming territory on the moon, which would complicate digging up parts of it and selling it.

Gabrynowicz, the space law expert, said even a scientific outpost that wanted to dig up lunar ice for study will require an international agreement first. Anything for commercial purposes would be more controversial. Some nations, including the United States and Luxembourg, have passed national laws granting their citizens property rights over any materials extracted on celestial bodies, but these laws differ in important aspects and don’t form a universal framework for lunar mining.

Science fiction author Andy Weir, who wrote The Martian, tackled these economic questions in his novel Artemis. His fictional lunar city had a tourism-based economy, which he estimated would be possible if advancements in space travel brought the cost of visiting the moon down to $70,000 per person—nearly an order of magnitude less expensive than today’s very limited selection of space-tourism experiences, but an improvement many believe is possible.

One reason many experts are optimistic is the new group of private space companies, such as Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin, which are developing new launch systems and have unveiled plans for sending explorers and settlers to other celestial bodies.

“Once the cost of sending people to the moon is driven down low enough that middle-class people can do it as a vacation, then we’ll have cities on the moon,” Weir wrote in an email to CityLab. “With companies like SpaceX and Boeing competing to drive down the cost of getting mass into orbit, the cost of spaceflight will go down and down.”

But Moon Cities Will Happen

Despite all the obstacles that have prevented lunar settlement in the half-century since Apollo, many experts believe the next 50 years will be more fruitful.

“I would think definitely by 2030 we’ll have astronauts on the moon—maybe not on a permanent basis, but cycling back and forth like we do with the space station,” said Benaroya.

David Warmflash, an astrobiologist and the author of a recent book about the moon, was less optimistic about the timeline but agreed some form of lunar settlement is likely in the future.

“If there was a public will to do it, the government wants to do it, industry wants to do it, and the people want to do it and aren’t going to vote out the politicians who say they want to do it, in under a decade we could have a really nice base on the moon,” he said.

A permanent settlement is not part of NASA’s current plan to return humans to the moon, but the space agency does want its next visit to establish a more-enduring foothold on the lunar surface. “While we hope to build a sustained human presence, we will have ongoing missions with crew rotations to bring our astronauts back to our home planet, Earth,” said Gina Anderson with NASA’s Office of Communications, in an email. “We have said we are ‘going to stay,’ and that means establishing scientific outposts similar to Antarctica or the International Space Station, where astronauts and robotic explorers can spend months living and working in ‘exploration zones’ with a mix of scientific interest and life-sustaining resources.”

Actual cities on the moon, with ordinary civilians living and working permanently, are likely much further in the future. Benaroya predicted they would happen—but not for a century or more.

Inflatable Bases and Lava Tubes

When humans do eventually establish permanent lunar settlements, they’re not likely to look very much like Earth cities, because of the unique demands of the harsh environment. Human habitations will need serious radiation shielding as well as air, food, and water.

“The fact that there’s no atmosphere means we need to pressurize our structure like we do submarines so people can live inside without their spacesuits,” said Benaroya, who has studied the engineering of lunar settlement.

Initial bases are likely to be like the International Space Station: pressurized metal tubes or cylinders, on or under the moon’s surface. Inflatable bases could also be used to provide much larger interior areas, if the technology is ready in time, Benaroya said. Whichever approach is used, the structure will likely need to be mostly underground for protection.

Another potential for long-term settlement is to use some of the large lava tubes under the moon’s surface, as large as several hundred feet in diameter. Sealing off the mouths of those underground caves could provide ready-built protection from meteors and radiation. More tantalizingly, Warmflash said, lava tubes could be terraformed to create sealed Earthlike environments. (Some thinkers have proposed ways to make the moon’s surface itself livable, but if even possible, these would likely take centuries of expensive work to accomplish, including crashing comets into the moon’s surface.)

Socially, the first lunar settlements are likely to be hardscrabble scientific research stations, such as McMurdo Station and Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. “In the beginning, it’s going to be almost exactly like Antarctica,” Warmflash said. “You’ve got people living indoors in an artificial environment where they’re almost totally dependent on technology, and they’ll rotate in or out every few weeks or months.”

But eventually, Head predicted, the experience of living short-term on the moon will help humans design the kind of homes and cities needed for more permanent lunar residency. And when they do, things will get interesting.

Who Gets to Be the Moon Mayor?

A host of political and legal questions will emerge during this process. Initial bases may be administered by national governments back in Earth—or, in a more commercial future, by corporations—but permanent residents will certainly develop their own independent allegiances, especially once moon-babies are born and born and raised off-Earth. Historically, remote settlements tended to grow independent from their countries of origin as they grew more self-sufficient and generations passed. Gabrynowicz expected that will “happen in space, too.”

“If you have a number of generations of people who are born on the moon or on Mars, they will at some point think of the Earth as that place where their ancestors came from, but they themselves are not Earthlings, because they themselves did not come from there,” she said.

This question of political independence will likely be complicated. “I suspect that’s going to be going on for a while,” said Abraham, the science fiction author. “Even if there is a separate culture, even if there is a separate sense of identity, the economic and political powers that delineate political governance, those are hard to shrug off.”

Maybe We Should Worry about Earth Cities, Too

During the Apollo program, racing the Soviets to the moon was a motivated in large part by the political rivalry between those two superpowers. A half-century later, the players in that drama have changed dramatically, and humanity’s home planet faces a host of life-threatening human-caused challenges. But Head argues that space exploration and settlement can still provide meaning and inspiration on both the individual and national level.

“Human imagination and the spirit of exploration is something that really needs to be cultivated and encouraged,” he said.

Given the range of threats to human civilization, from climate change and nuclear weapons to asteroid strikes or a reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field, many believe that humans need to eventually become “a multi-planet species” in order to survive. That’s also a theme echoed by the tech entrepreneurs funding private spaceflight efforts.

“If we only stay on this planet, we’re going to go extinct in geologically a short period of time,” said Warmflash. “We’re not really good at thinking over long periods of time as humans. Even if we look at the time scale of since the emergence of civilization ... a lot can happen in several thousand years.”