The Mysterious Exploding Asteroid

Jurik Peter/Shutterstock.com

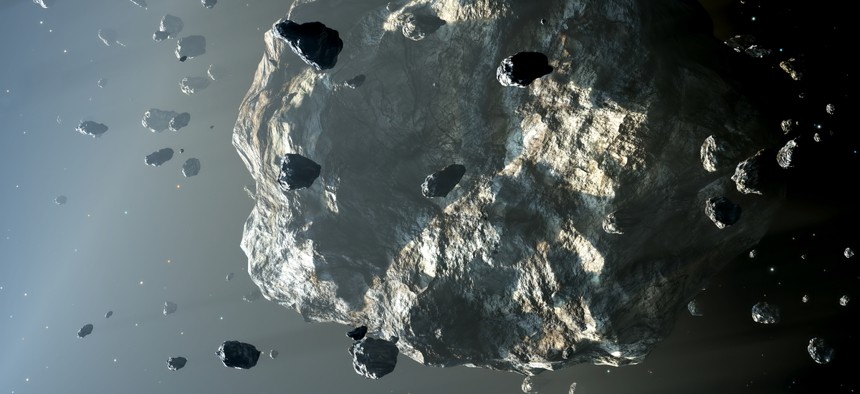

A NASA spacecraft reached a space rock and found it orbited by tiny moons—a phenomenon that “has never been seen before in any solar-system object.”

Billions of years ago, something—perhaps the vibrations of an exploding star—jostled a cloud of cosmic gas and dust suspended in space. The cloud collapsed on itself and flattened into a spinning disk. The center grew heavy and ignited, forming our sun. The stuff that remained ricocheted, collided, and congealed. The biggest clumps of space stuff smoothed into spheres—the planets and moons. The smallest, the asteroids and comets, stayed as they were, like crumbs left over from an elaborate feast.

And right now one of those crumbs is exploding.

An asteroid named Bennu has been caught spewing particles into space—hundreds of gravel-size bits, hurtling from the surface at high speed.

The tiny explosions were spotted by a NASA spacecraft named OSIRIS-REx. The probe settled into an orbit around the asteroid in late December and noticed the first ejection within days. Over the next two months, OSIRIS-REx observed nearly a dozen of these events. And more are still being detected.

“It’s one of the biggest surprises of my scientific career,” says Dante Lauretta, the lead investigator of the mission.

The solar system is littered with asteroids, from near Earth to the edges well beyond Pluto. Bennu, a blob-shaped object slightly larger in diameter than the height of the Empire State Building, resides close by, and its orbit occasionally crosses paths with the orbit of Earth.

But particle-spewing asteroids are extremely rare. Only about a dozen of the 800,000 known asteroids in the solar system are classified as “active” like this. That’s why, when NASA launched a spacecraft to study Bennu, scientists didn’t expect it would be one of them. The numbers were against them.

Astronomers don’t know what’s causing the ejections, but they have several potential explanations. Some asteroids spin so fast that pieces of them start to fly apart. Others are sideswiped by floating debris, a collision that can expose icy particles buried beneath the surface and sweep them into space. Andy Rivkin, a planetary astronomer at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory who studies asteroids, suspects the sun might have something to do with it. When the light hits a rocky object without a protective magnetic field—such as Earth—the particles become positively charged, while those in the shade remain negatively charged.

“Near the terminator or the shadows, the charge difference leads to a voltage difference that can be really huge,” Rivkin says. “On the moon, this effect has been seen to levitate dust. On asteroids … who knows what happens.”

The OSIRIS-REx team says the plumes of particles aren’t dangerous to the spacecraft. Some particles rain down on Bennu. Others are thrown deeper into space, beyond the tug of the asteroid’s gravity. Still others get stuck in between and settle into an orbit around Bennu, creating a new population of tiny moons around the asteroid. “That has never been seen before in any solar-system object,” Lauretta says.

Some of the evicted particles might eventually make their way to Earth and plunge into the planet’s atmosphere in a dazzling meteor shower. Lauretta predicts the particles could reach Earth as soon as September.

The past few months of observations have turned up other surprises. Scientists predicted the surface of Bennu would be quite smooth. Instead, it’s rugged and cluttered with boulders. The textured terrain presents a new challenge to the OSIRIS-REx team. The spacecraft hovers safely around the asteroid, but it was designed to swoop in and collect samples of the surface material. Scientists and engineers say they will now reconsider potential landing spots for the maneuver. After scooping up some asteroid grains, OSIRIS-REx will depart Bennu and head back to Earth. The samples will arrive in 2023, and scientists can’t wait to get their hands on them.

Unlike planets and moons, asteroids have remained virtually unchanged since the beginning of the solar system, preserved by the vacuum of space. Scientists suspect that asteroids such as Bennu, which is covered in water-rich minerals, delivered some of the water present on Earth today, though they’re not sure on the specifics. (Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft found evidence that another asteroid, named Ryugu, had less water than expected, according to newly released results from the mission.) To study these objects is to explore the past of our cosmic neighborhood. “It’s almost like doing archaeology,” says Eva Lilly, a scientist at the Planetary Science Institute.

Scientists have another motive in their research: self-preservation. Because of its close proximity to Earth, Bennu is classified as a potentially hazardous asteroid. The risk isn’t immediate; scientists estimate a 1-in-2,700 chance of an impact late in the 21st century. But they want to be prepared, for the sake of future generations.

“In case there is, one day, an asteroid heading toward Earth, we want to know what we are dealing with,” says Lucille Le Corre, a scientist at the Planetary Science Institute who works on the OSIRIS-REx mission.

The rocky relics of the ancient past might also hold some clues about the solar system’s future.

“The more that we can understand the early parts of the solar system and the evolution that we’ve taken to get to this point in our history, the more we can understand what happens next,” says Cristina Thomas, an assistant professor of astronomy and planetary science at Northern Arizona University.

What happens next?

“That’s a good question,” she says. “Who knows?”