Is the Revolution of 3D-Printed Building Getting Closer?

asharkyu/Shutterstock.com

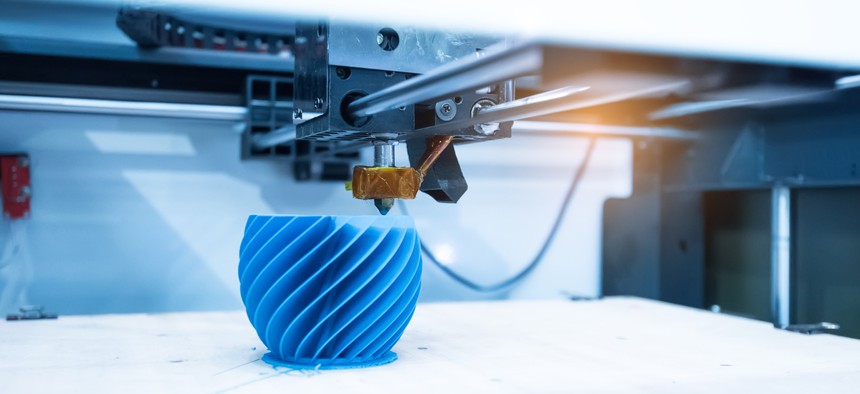

3D printing was expected to transform architecture and construction, but uptake has been slow. Could that be changing?

There’s a soft buzzing sound coming from a tent that stands next to a hotel in a village in the Netherlands. Inside, an arm attached to a large orange-and-black printer on tracks applies concrete to a disc, like frosting on a cake. This is followed by a second layer. A man operates the laptop that’s connected to the printer.

Here in Teuge, about 60 miles east of Amsterdam, a small building is being assembled layer by layer with a 3D printer.

The building will be called De Vergaderfabriek, Dutch for “the Meeting Factory.” According to the companies behind the project, it will be the world’s first 3D-printed meeting space. The roughly 1,000-square-foot structure was supposed to be done months ago, but a neighbor objected to the project, which held it up. The local municipality also thought the original design wasn’t appropriate for the site, so the architect, Pim van Wylick, revised it, making the building smaller and shorter.

3D printing is sometimes hailed as a revolution for architecture and construction. Enthusiasts say the technology is much faster and cheaper than conventional building, and that it has a smaller environmental footprint. But so far, machine-printed buildings have not materialized in significant numbers. Most examples are one-offs and are not fully habitable. The technology is hard to reconcile with building codes, and large-scale printers are scarce and expensive.

However, robotic architecture is still maturing. Recent examples include an office space in Copenhagen (2017) and a micro-home in Amsterdam (2016). Last March, an Austin startup named Icon debuted a tiny 3D-printed house, built in less than 48 hours, at South by Southwest. The company has partnered with the non-profit New Story on a plan to construct dozens of 3D-printed homes in El Salvador.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Marine Corps has 3D-printed a 500-square-foot concrete barracks hut, with an eye to robots eventually building military structures on demand. And last month, two companies announced a 3D-printed homebuilding system called We Print Houses, which they intend to license to builders and contractors around the U.S.

In the breakfast room next to the tent in Teuge on this January morning, Arvid Prigge, who runs the De Slaapfabriek boutique hotel and a conference and training center called Centre4Moods with his wife Marjo, speaks enthusiastically to members of the press. He already hosts corporate meetings and training courses, but needs more space for them, he explains. “If we were going to create a new building, it had to be special,” he says. “Something iconic and unusual.” Prigge’s interest in 3D printing was sparked several years ago when he read about a 3D-printed building in China.

The Meeting Factory sits near a small airport, and its design was inspired by aviation. From above, it resembles the rotating blades of a jet engine. Prigge believes the curved walls will create a sense of equality and safety that will enhance communication. Users will be able to choose from different 360-degree video projections, set to the music of their choice. “When you see a pine tree on the wall, you’ll also smell pine needles,” Prigge says, “and when you see a tropical beach, you’ll smell coconut. … A meeting room with bare walls isn’t very inspirational.”

Inside the tent, the first two ribbed walls are ready. Twelve more to go. “We created a specific type of mortar that hardens within a day and that won’t shrink, expand, or collapse,” says Berry Hendriks of CyBe Construction, which oversaw the printing process. “We developed special algorithms to print the double-curved walls. It was pretty complicated, but we conducted research beforehand to determine whether it was feasible.”

The employees operating the printer, controller, and mixing device are deep in concentration. “Of course, you only have one chance to get it right,” explains Hendriks. “You can’t forget anything. After we’ve prepared and checked everything—the temperature, the consistency of the material, the location of the wall, the electricity and water—we press play and the system works its magic.”

“This project was fun, but a headache as well,” admits the architect, van Wylick. “You’d think a building of just a hundred square meters wouldn’t be much work, but the many regulations made it challenging.”

CyBe, which has been involved in 3D printing since 2016, recently printed an 860-square-foot, single-bedroom house in Saudi Arabia for €50,000 ($57,000). Hendriks declined to reveal the cost of the Meeting Factory, but said that 3D printing is roughly half as expensive as conventional building.

3D printing is often said to be more sustainable and less wasteful than conventional construction. Researchers at the Eindhoven University of Technology estimated that building the Meeting Factory will generate 40 percent less CO₂ compared to the usual methods. But the environmental implications of 3D printing are not yet fully known.

The printing in Teuge was expected to last 10 days, but has taken a few days longer so far (it is expected to finish imminently). “It wasn’t our goal to do it as fast as possible,” said Hugo Jager, the project leader from consultancy firm Revelating. “It was more important to do it right. In any case, the whole process will be much faster and cheaper next time.” Several houses are set to be 3D-printed later this year in the Dutch city of Eindhoven, and the creators of the Meeting Factory believe 3D printing will become a reasonably standard building method within a short time.

The official opening of the building will take place this spring. A neighbor who will have a view of it from her living room (and who declined to give her name) said it doesn’t bother her. “I don’t know how 3D printing works, but at least it’s something new. The design seems unique and I think it will fit here,” she said.

Another local woman, walking by the construction site, was bemused. “I don’t understand how they got permission for something like this,” she said, adding: “The municipality usually fights you on something as insignificant as brick color.”