Quantum lag: Experts fret that the U.S. risks falling behind in computing power

Quantum computing could upend current cryptography standards, and experts are urging government to take an interest in the technology as it develops.

The promise, and threat, of quantum computing is still years away. But quantum experts fear a lack of government emphasis and coordination on research strategy could upend U.S. digital and national security.

"Global computing leadership is essentially up for grabs again," said Stephen Ezell, vice-president of global innovation policy at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation at a Sept. 12 event hosted by the Hudson Institute. "It's going to be the societies that marshal the optimal set of resources in terms of funding, talent, university research and commercialization that lead this transition."

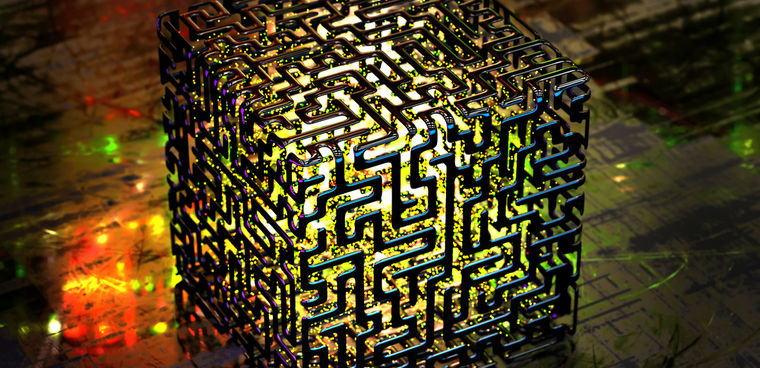

Quantum computing works by replacing the binary zeros and ones of conventional computing with multivariable quantum bits, radically increasing the speed of calculations and potentially threatening to make current computing and cryptography obsolete.

To frame the potential power of quantum technology, Ezell said, quantum computers "are potentially millions of times faster and more powerful than current computers."

The supercomputing power of future machines has sparked national security concerns.

Christopher Monroe, professor of physics at the University of Maryland, touted the capabilities of quantum computing — hacking, breaking codes at lightning fast speeds and storing immense amounts of data — but tempered, "this problem is really far away."

"I would make a prediction that it's way more than five years before we can break public key encryptions," he said. "I am afraid, though, if we don't find something in five or 10 years, we will never get to the billions of cubits you need to break codes and so forth."

As far as government's role in moving forward, Ezell lamented that "to date, [the U.S. has] not had any kind of national coordinated strategy" that other countries, such as China, do have.

Since 2014, China has surged past the United States in the number of patents related to quantum applications, Ezell noted.

While Monroe said he believes the threat of Chinese dominance is "overstated," he cautioned that shouldn't mean the U.S. can afford to neglect significant investment in quantum research and technologies.

"It's advanced far enough that we can identify a few fields that really need to develop a workforce," he said. "If nobody's going to pay for it, it's just not going to happen."

Congress is beginning to take an interest in the new technology. The House passed the National Quantum Initiative Act on Sept. 13 to begin to address a national strategy towards quantum.

The bill, sponsored by House Science Committee chairman Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas), directs the White House to implement a 10-year plan to accelerate quantum computing development. The measure would tap the expertise at the Department of Energy, the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the National Science Foundation in a $1.2 billion effort to jumpstart quantum research.