Bill calls for evaluation of jamming prisoners' illegal cell phones

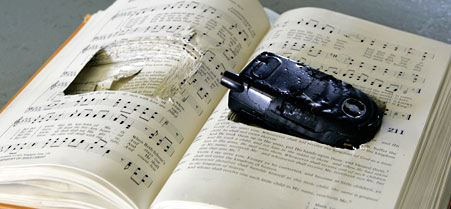

Prisoners use mobile phones to run drug rings, plan jail breaks, and intimidate judges and victims, but industry argues blocking signals could interfere with police radios.

Gangs use cell phones smuggled into prison to coordinate illegal activities, according to officials.

Gangs use cell phones smuggled into prison to coordinate illegal activities, according to officials.

A mega-spending bill the Senate plans to vote on this weekend would require three agencies evaluate deployment of wireless jamming or detection systems to crack down on prisoners' use of illicit cell phones, which many use to plan jail breaks and intimidate judges, lawyers and victims.

The use of illegal cell phones in prisons "is growing at an alarming rate," said Gary Maynard, secretary of the Public Safety and Correctional Services Department in Maryland, in testimony before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation in July. "In California, prison officials reported that they collected over 2,800 cell phones last year, two times the amount found the previous year."

Violent gangs use cell phones smuggled into prison to coordinate illegal activities inside and outside prisons, according to Maynard.

The jamming initiative is included in the 2010 Consolidated Appropriations Bill, which the House passed on Thursday and the Senate plans to vote on this weekend. It requires the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, and the Federal Communications Commission to work together to deploy the systems.

The bill marks the latest in a yearlong series of efforts to stop illegal cell phone use in prisons, all of which have run into fierce opposition from CTIA, a large trade association for the cell phone industry. The group argues that the 1934 Communications Act prohibits anyone from interfering with radio communications.

In January, the FCC approved a request by the District of Columbia to test for 90 minutes a cell phone jammer in the DC Jail. CTIA opposed the test in filing a petition to the federal Court of Appeals in the District. The association said even a limited test could cause "substantial harm to the rights of wireless service providers, their customers and the general public."

CTIA also appealed to FCC, which then reversed its decision to allow the test.

In addition, CTIA opposed the 2009 Safe Prisons Communications Act when Rep. Kevin Brady, R-Texas, and Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchinson, R-Texas, introduced it in January. The bill would allow prisons to petition FCC to operate wireless jammers.

Steve Largent, president and chef executive officer of CTIA, told a Senate hearing in July that while the cell phone industry wants to help block cell phones in prisons, "the jamming of wireless signals is not a panacea and raises potentially serious concerns that must be taken into account as Congress contemplates how to address this issue."

Jammers in prisons could interfere with radios used by police or fire units responding to calls for help, Largent said. He suggested a better approach would be to use systems that can detect illicit cell phones in prisons and use software that allows calls from only authorized phones in a prison.

The cell phone industry understands the use of cell phones by prisoners "is a problem and we want to be part of the solution," said Brian Josef, a CTIA spokesman. He said CTIA supports Congress exploring all the means to stop illicit cell phones.

Margaret Boles, an AT&T spokeswoman, said, "We fully support efforts to find a solution that prevents unlawful use and possession by the incarcerated while also maintaining public safety access to critical wireless communications in the areas surrounding correctional facilities."

NEXT STORY: So Many Earmarks, So Little Time