FBI wants deeper conversation on encryption

The head of the FBI wants a less strident discussion about the strong encryption technology that is becoming standard on electronic devices and hampering investigative efforts.

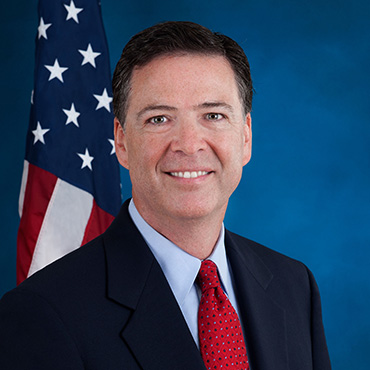

Although terrorists don't rank high on FBI director James Comey's list of top cyberthreats -- state-sponsored groups, organized crime and hacktivists are all greater concerns -- the bureau's ability to track terrorists through their digital devices remains a priority.

"We need to have a national conversation" over how strong encryption is spreading across all devices, narrowing the agency's ability to catch terrorists, said Comey in remarks at Symantec's Government Symposium on Aug. 30.

Comey's agency has been struggling to get access to a growing number of encrypted devices, like cell phones, in critical cases. Its ability to help states with investigations involving encrypted devices is also crimped, he said, with over 600 devices submitted by states for analysis waiting in the wings.

The agency's most public fight over encryption has been with Apple over a smartphone that belonged to Syed Rizwan Farook, who with his wife, Tashfeen Malik, killed 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif., last December.

Comey said he is looking to restart a national conversation over strong encryption after the presidential election in November. Comey first identified the "going dark" problem for law enforcement in a 2014 speech, and has since been looking to spur cooperation among technology manufacturers and providers, with little success.

Nation states, particularly China, are apparently taking FBI's warning that it's not in their best interest to steal and profit from U.S. data. Comey said the agency's push to identify Chinese hackers who stole U.S. data was having an effect, as is a year-old cybersecurity agreement with China.

Recent reports of hacks on state election system facilities, however, muddy that picture a little. While the hacks into Illinois and Arizona election data have been confirmed by FBI reports, it's unclear who the hackers were. Some have attributed the intrusions to Russia and others to unaffiliated cyberthieves.

Comey declined direct comment on the election hacks, but said his agency "takes very seriously any effort, especially by a nation state, that moves beyond information collection" and moves to influence U.S. government operations.

Organizations like the Islamic State, he said, have proven themselves effective in using the Internet to reach inside countries for recruits and to inspire action. It's only logical, he added, that they will move towards cyberattacks.

Computer intrusion "has to be the future of terror," Comey said. "Surely they will turn to photons" in their dogged effort to disrupt western societies.

Ubiquitous, strong encryption deployed routinely on all electronic devices, he said, will complicate efforts to battle that threat.

Industry's argument for absolute privacy for devices, Comey said, is unrealistic. "It's a seductive argument," he admitted, but noted that U.S. law has never promised absolute privacy, and historically has allowed courts and judges to grant warrants for all manner of private spaces when there is evidence of criminal activity. The advent of absolute privacy "shatters that bargain," he said.

The arguments by federal law enforcement for access to encrypted devices have been vilified and emotionally charged by opponents, he said, adding: "Intense emotion blunts thoughtful exchanges."

After the election, Comey said, the country has to have a serious, unemotional discussion about the issue. "There are no evil people in this discussion," he said. Both sides value the ideals of freedom and privacy and even strong encryption.

"We love strong encryption protections," he said, "but absolute user control of data is not strong encryption."

The discussion Comey seeks will probably remain spirited, however. In a tech panel following his remarks, privacy advocates discounted the FBI director's assertion that encryption was harming surveillance and hampering investigative capabilities..

With the growing Internet of Things, widespread surveillance cameras and other technologies, "it's the golden age of surveillance," said Nuala O'Connor, president and chief executive of the Center for Democracy and Technology.

"We want the FBI to keep us safe," she said, "but building a backdoor -- a defect -- into products isn't the way to solve the problem."

"It's not the keys to one apartment. They want the master key to the whole building."