Why cyber took a back seat in Beijing

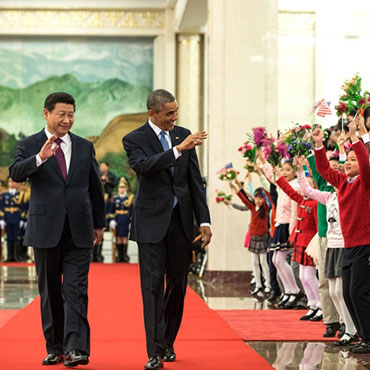

In advance of President Barack Obama’s meeting with China President Xi Jinping, White House advisers made a lot of noise about getting tough with China on cybersecurity. But the topic was barely mentioned by either side after the talks.

President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping discussed cybersecurity issues, Obama said, but pre-summit promises of candid negotiations brought little apparent progress.

In advance of President Barack Obama's Nov. 11 meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Deputy National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes implied that Obama would be blunt with Xi on what the U.S. sees as China's transgressions in cyberspace, and also try to revive a bilateral working group on the issue. Obama may well have pushed for a breakthrough on cybersecurity in his five-hour meeting with Xi, but one was not forthcoming.

A big climate accord and visa issues overshadowed cybersecurity in the announcements at the summit, and the lack of anything worth trumpeting on cybersecurity illustrates just how thorny a bilateral issue it is.

Sino-American cyber relations have over the last several months been clouded by the revelations of former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden of U.S. hacking of Chinese assets, and by China's alleged repeated theft of U.S. intellectual property.

In the last week alone, media reports have indicated China is behind two hacks of U.S. government agencies – the U.S. Postal Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

"When we see things on cybersecurity where we have Chinese actions that disadvantage U.S. businesses or steal intellectual property, we're going to be very candid about that," Rhodes said at a press briefing before the Obama-Xi meeting.

And in a post-meeting press conference, Obama briefly touched on the issue. "I stressed the importance of protecting intellectual property as well as trade secrets, especially against cyber threats," he said of his meeting with Xi.

When FCW asked the White House for further details on Obama and Xi's discussion of cybersecurity, a spokesperson said it was a question best answered by advisers traveling with the president, who were unavailable.

Michael McNerney, who was a cybersecurity policy adviser at the Defense Department from 2010 to 2012, said he was not surprised by the lack of tangible outcomes on cybersecurity, given the obstacles.

"The fallout from Snowden makes those conversations very difficult," said McNerney, who is a fellow at the Truman National Security Project. "If we go to China and say, 'Stop spying on us,' they're going to say, 'Well, stop spying on us.' It's now a much harder conversation to have." In a story published in June 2013, Snowden told the South China Morning Post that the NSA had hacked computers at Tsinghua University, a prominent university in Beijing.

Good cop, bad cop

Cybersecurity is one of the most important issues in U.S.-China relations, and also the one that affects all others, from trade relations to national security. That is one reason the two countries set up a cybersecurity working group last year to air their differences on the subject.

But China canceled the working group after the Justice Department indicted five Chinese military officers on charges of cyber espionage in May. Secretary of State John Kerry's July visit to Beijing failed to revive the working group and further underlined differences in the two countries' positions. Kerry's public comments in Beijing lamented intellectual property theft, while Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi warned against using cyberspace as "a tool for damaging the interests of other countries."

Frank Cilluffo, director of the Homeland Security Policy Institute at George Washington University, says U.S. calls for China to stop targeting U.S. intellectual property in cyberspace have had "little, if any, effect in terms of inducing … changes in [China's] behavior."

But whether or not the cybersecurity working group was yielding policy outcomes, Cilluffo said, "I do believe that the stakes in this domain are so high that it is important that we at least have vehicles that we can communicate in the event of escalation."

In the absence of a working group, the Obama administration looks set to continue its good-cop-bad-cop approach to China in cyberspace.

DOJ officials have indicated more indictments could come, which would likely offend China further and diminish chances of the working group restarting. That punitive approach contrasts with closed-door meetings on cybersecurity like the one Obama and Xi had this week.

Relations with China are an important part of U.S. efforts to build international norms in cyberspace, and Beijing has shown at least some willingness to go along with Washington on the issue.

China last year signed on to a report by the United Nations Group of Government Experts that advocated applying the UN Charter and international law to cyberspace, as Adam Segal, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, has noted.

But there is still a big gulf between how Beijing and Washington see the issue, according to McNerney.

"Cybersecurity is like all things to all people. To the Chinese government, cybersecurity is as much about stifling dissenting opinions among its populace as it is securing their networks," he said. "So there's a lot of difficulty in coming to a meeting of the minds between the two countries because of that."