Trump's Advisers Want to Return Humans to the Moon in 3 Years

NASA

The plan could dramatically shift the mission of the space agency, prioritizing low-Earth orbit activity over distant exploration.

The Obama administration wanted to send humans to Mars. But the Trump administration wants to put them back on the moon first, and quickly.

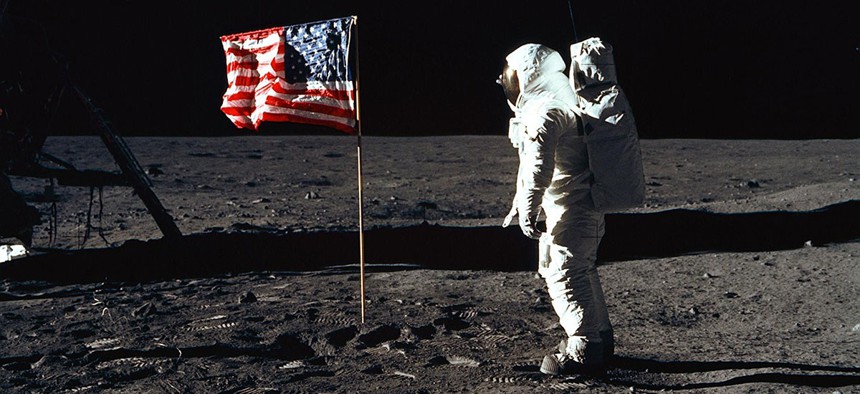

That ambition is inside internal documents reported by Politico on Thursday that describe what would be a dramatic shift in mission for NASA. According to the documents, created by the transition team assigned to the agency, President Donald Trump’s advisers want NASA to send humans to the moon three years from now, nearly five decades since the last astronaut left his footprints there.

NASA would focus on boosting human activity in the cislunar region—the space between the Earth and the moon—as opposed to venturing deeper into the solar system. The space agency’s main goal, it says, should be “the large-scale economic development of space.”

“NASA’s new strategy will prioritize economic growth and the organic creation of new industries and private sector jobs, over ‘exploration’ and other esoteric activities,” explains a summary of what’s next for NASA in the documents. “Done correctly, this could create a trillion-dollar per year space economy, dominated by America.”

It’s not surprising for a new administration to want to take NASA in a different direction so soon after its arrival in Washington. Eight years ago, Barack Obama canceled the Constellation program, created under George W. Bush, which planned to return humans to the moon by 2020. Obama believed the program was too expensive and that NASA had “lost focus,” especially as it began to wind down the space-shuttle program, the country’s pioneering pride and joy. He told NASA to put people on Mars by the 2030s, and lasso an asteroid somewhere along the way.

If the Trump administration’s picks for space-policy advisers are an indication, the country will remain on a long-term mission to Mars. Wrenching the idea of a Martian journey from the American public after two terms of successful NASA public-relations campaigns and Hollywood space movies would be a difficult exercise.

Plus, there’s strong bipartisan agreement in Congress that the Mars deadline can’t move. But the next four to eight years may see an aggressive push for more movements in Earth’s backyard, where hundreds of satellites and the International Space Station reside.

Politico reports Trump advisers want “private American astronauts, on private space ships, circling the Moon by 2020.” That vision puts a lot of faith into private spaceflight companies developing and testing rockets capable of carrying payloads and people to low-Earth orbit. The company SpaceX especially stands to benefit from this ambition, because its CEO, Elon Musk, meets often with Trump as a member of the president’s advisory council of business leaders.

Increased investment in private-public partnerships in human spaceflight would actually be an expansion of Obama’s hopes for NASA. But spaceflight is blind to the origins of funding, both private and federal. SpaceX and Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’s spaceflight company, are already behind schedule on perfecting the rockets they’ll let NASA use to carry astronauts into space next year. SpaceX has seen two rockets blow up in less than two years. The funding isn’t there yet, either; Trump has not announced a budget proposal for the next fiscal year, a process that usually begins in February.

“This is not a bad idea, but the timeline that’s implied in this article would be an unprecedented speed,” Casey Dreier, director of space policy at the Planetary Society in California, said of the Trump advisers’ ambitions. “Just because you have private companies involved doesn’t mean you can ignore physics or the harsh environment of space.”

The president’s advisers favor these private spaceflight companies, considered “New Space,” over “Old Space” contractors, like Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

“We have to be seen giving ‘Old Space’ a fair and balanced shot at proving they are better and cheaper than commercial,” the documents say. This likely won’t sit well with Congress. In 2010, Congress instructed NASA to develop a heavy, expendable launch vehicle that would replace the shuttle program and carry transport astronauts into orbit. The Space Launch System, or SLS, is being manufactured by Boeing and Lockheed Martin, with plans for a first flight in late 2018.

The SLS is costing billions of dollars, far more than the rocket technology being developed by private companies, but it employs tens of thousands of people. Lawmakers, Dreier says, won’t be jumping the idea of killing jobs in their districts in favor of sending humans to the moons with rockets made somewhere else. The closer the Trump administration gets to the private spaceflight company, the greater the risk of alienating some of his Republican allies in Congress.

The Trump documents set another goal for 2020. By that year, the United States will see “private lunar landers staking out de-facto ‘property rights’ for America on the moon.” Claiming any sovereignty of the moon is a violation of the United Nations Outer Space Treaty, the set of principles that govern the use of outer space, and which have been observed by dozens of nations since the late 1960s.

Planting an American flag on the lunar surface is one thing, but marking territory is another, and carries geopolitical implications. This ambition would put the U.S. in some competition with China, which plans to ramp up its own cislunar activity in the next decade, and wants to land a rover on the far side of the moon in 2018, a first for any spacefaring nation.

The Trump administration is still several months away from picking NASA’s next administrator, but the documents Politico obtained suggest Jim Bridenstine, the Republican congressman from Oklahoma, is at the top of the list. Rumors that Bridenstine wants the job have swirled since the election. The congressman has proposed detailed legislation for NASA policies and extolled the benefits of lunar missions in blog posts. The rumors intensified this week after his remarks at the annual Commercial Space Transportation Conference in Washington, D.C.

“It is our job to make America great again in space,” he said, adding the U.S. should use its “secret weapon,” the commercial space industry. Bridenstine’s office told me this week he would be “honored” to serve in the new administration if Trump asked.

Dreier cautions the latest glimpse of potential Trump space policy may be just that—a peek into the internal debate over NASA’s mission, rather than a clear roadmap for the space agency’s future. But there’s a pretty glaring omission hard to miss: science.

The documents, as reported, don’t make any mention of the various scientific projects that will punctuate Trump’s first term, like the galaxy-searching James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2018, or the next Mars rover, preparing to lift off in 2020, or the first lander mission to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, which scientists are currently trying to figure out. Human spaceflight programs are expensive, and risk overshadowing such projects.

“Science always tends to suffer when human spaceflight programs go over budget,” Dreier says.