Via the Moon, a theory of life on Mars

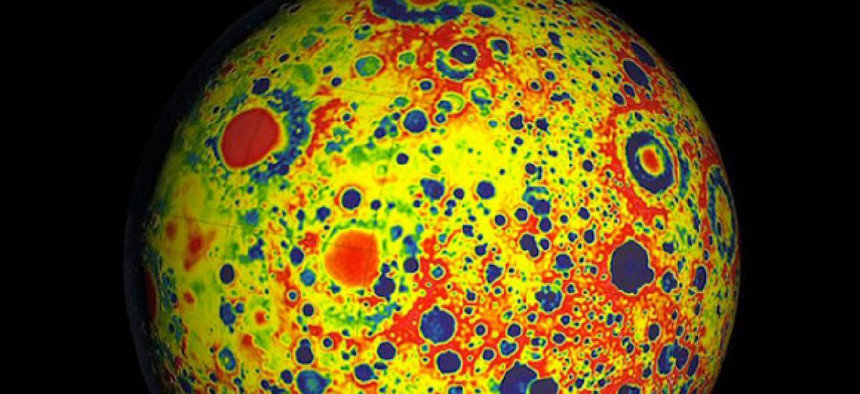

A gravitational map of the moon, depicting newly quantified lunar mass: Red indicates more massive areas and blue indicates less mass. NASA/JPL

NASA captures, quite literally, gravity's rainbow.

Scientists care about the moon in part because it is the moon -- our moon. But they care about it, also, because its body is in some ways a proxy for our Earth's: Its surface, like ours, bears the scars of a long existence in our little corner of the Milky Way. And new research suggests that that existence might have been much more violent -- and perhaps more hospitable to life -- than we humans initially believed. Yes.

The story begins, officially, around five years ago. In 2007, the Japanese lunar satellite Kaguyareleased two small probes into orbit around the moon. Those satellites, working in tandem, created the first gravity map of the far side of the moon -- a chart that showed, in color-coded detail, the variations in mass on our nearest planetary neighbor.

The same year, NASA announced plans for a similar mission: the launch of twin spacecraft that would spend several months doing their own moon-mapping work, measuring the lunar gravity field in unprecedented detail. In late 2011, NASA began that mission, sending a pair of spacecraft -- collectively known as GRAIL (Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory) -- to orbit the lunar surface. The pair of satellites (named, awesomely, Ebb and Flow) fly in formation around the moon, sending each other -- and Earth -- microwave measurements of our only natural satellite. The twin vehicles, each about the size of a washing machine, work by detecting tiny changes in the distance between them -- variations caused by lunar mountains, craters, and subsurface mass concentrations.

NEXT STORY: How to take the 'social' out of social media