Navy joins effort to track moving oil slick in the Gulf

The service deploys systems to measure currents, water temperature, salinity and organic matter such as oil from the surface to depths of thousands of feet to develop a model of the evolving spill and where it's headed.

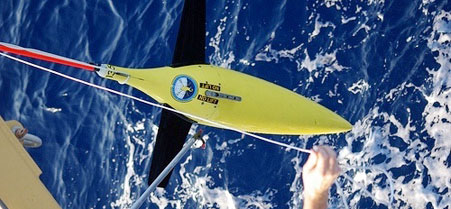

Seagliders "fly" through the water to measure temperature, salinity and traces of oil in Gulf waters.

Seagliders "fly" through the water to measure temperature, salinity and traces of oil in Gulf waters.

To support the federal response to the oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, the Naval Oceanographic Office has deployed sensor systems to monitor surface currents and measure physical properties of the deeper Gulf waters to better analyze the disbursement of the millions of barrels of oil that has poured into the environment.

The instruments support a modeling program in the Gulf, providing information to the national response team's effort to assess the status and drift of an oil slick now the size of Maryland, said Capt. Brian Brown, commanding officer of the Naval Oceanographic Office at Stennis Space Center in Mississippi.

His organization is part of a joint federal effort that includes a number of agencies, primarily the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The mission has personal implications for the 1,000 military, civilian and contract workers at the office because "this is our backyard," Brown said. "We work and live on the Gulf. Many of our employees grew up here."

With information from sea sensors and satellites, the office provides the Defense Department and other federal agencies a global ocean forecast model that is useful for 72 hours.

The model, which has a 7-mile grid resolution, includes the Gulf of Mexico and provides information on currents and ocean structure from the surface of the sea down to the bottom of the ocean, Brown said.

To better understand and predict smaller scale ocean circulations in the Gulf of Mexico as part of the response to the oil spill, the Naval Oceanographic Office has accelerated the planned development of a higher resolution 1.5-mile grid resolution model, currently undergoing final verification and validation.

Both models depend on data obtained by measuring key variables, including currents, temperature and salinity both on and below the surface of the ocean. The Navy recently deployed 20 instruments in the Gulf of Mexico with support from NOAA to gather additional data for the higher resolution model, Brown said.

These include two subsurface Seagliders deployed from the NOAA ship Thomas Jefferson this week, said Dan Berkshire, technical lead for the ocean measurements department at the Naval Oceanographic Office.

Similar to aerial gliders, the 110-pound, 9-foot long gliders "fly" through the sea on predetermined compass headings, using internal bladders to adjust their buoyancy and sensors to measure temperatures and salinities from the surface to depths of 3,200 feet. A fluorometer was installed on each glider to measure dissolved organic material in the sea, including potential oil.

Berkshire said the gliders surface every six hours to transmit the data they have collected via a built-in iridium satellite telephone satellite chip to a Defense satellite gateway in Hawaii, which then relays the information back to the Naval Oceanographic Office in near real time. While the Seaglider is on the surface, Berkshire said it is updated via satellite with a new course.

Brown said the Naval Oceanographic Office also deployed six subsurface APEX profiling floats, which gather the same data the Seagliders collect, as well as 12 Davis drifting surface buoys to measure surface ocean currents.

But he pointed out the two systems, unlike the Seagliders, are at the mercy of currents to control their location. Both systems transmit their data via the Argos satellite system operated by NOAA, NASA and the French governments space agency in a partnership. The data is available to the global oceanographic community via the World Meteorological Organization's Global Telecommunications Service. The surface drifters provide positions several times a day and the profiling floats send observations every five days.

The data the seagliders transmits is fed to the supercomputing complex at Stennis, which includes a 12,872 processor Cray machine capable of 117 trillion operations per second and a 5,312 processor IBM machine capable of 92 million operations per second, said Robert Lorens, director of the ocean prediction department at the Naval Oceanographic Office.

The supercomputers use the data to run in a sophisticated ocean forecast model to produce representations of currents and forecast ocean structure. The data is stored in standard oceanographic file formats that can be displayed as standalone graphics, incorporated into geospatial information systems or a variety of other systems, Brown said.

Lorens said the Navy, with its ocean modeling and supporting data collection program, can assist the national response team's efforts in determining the long-term transport of the oil in the Gulf of Mexico, including whether the the area's loop current could carry oil around the southern tip of Florida and up its eastern coast.

There is always an inherent risk in operating in the maritime environment, especially beneath the ocean surface. Brown said he is concerned the oil could render the seagliders and their sensors close to inoperable, but he believes the potential benefits outweigh the risks.

NEXT STORY: America's First Black Aviator