The imitation game

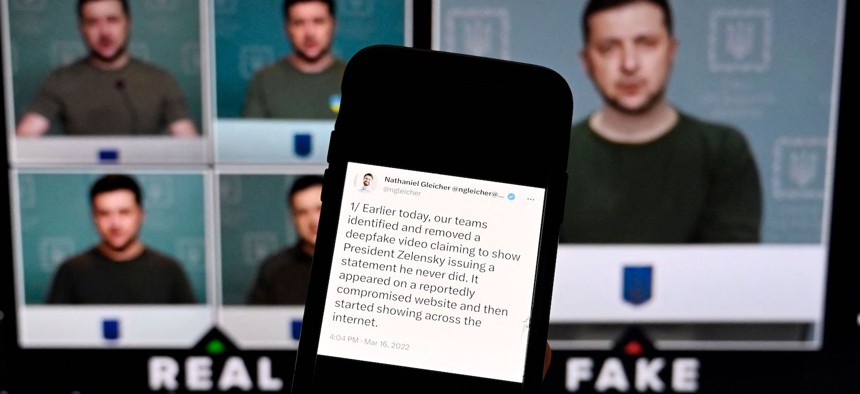

This illustration photo taken on January 30, 2023 shows a phone screen displaying a statement from the head of security policy at META with a fake video (R) of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky calling on his soldiers to lay down their weapons shown in the background. Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty Images

The emergence of low-cost deepfakes has led to a high-stakes race to develop technologies that can detect and label synthetic media.

SPECIAL TO NEXTGOV/FCW

The threat of deepfakes started to hit home for policymakers in 2023.

The potential malicious uses of the technology were always clear. But over the past year governments have witnessed a democratization of AI-based tools that lowered the barriers to entry for bad actors and turbocharged the use of synthetically generated media in areas like financial fraud, nonconsensual pornography and, increasingly, politics.

While AI systems continue to get better at creating fake videos, images and audio, Congress has yet to coalesce around meaningful legislation to curb or regulate the tech. Meanwhile, federal agencies are throwing hundreds of millions of dollars into funding detection and authentication technologies that most experts say are helpful but not yet sufficient.

Some lawmakers believe the First Amendment limits the power of federal agencies to act in this area. Rep. Ted Lieu, D-Calif., told Nextgov/FCW that, for now, the best weapons against fake media are more aggressive moderation policies at social media companies, limits on the use of deepfakes by political actors and teaching Americans to be more skeptical of media they come across in the wild.

“I think it’d be very difficult, for example, to pass any sort of law that says a person in the basement of their home who decides to do deepfakes and put that in an app … that somehow that person is going to be prosecuted or regulated,” Lieu said.

Others are looking for ways to harness bipartisan concern among legislators about synthetic media. Sen. Todd Young, R-Ind., has said that while he worries about the impact of AI regulations on American businesses, most people in Congress believe the government has a role to play in limiting harms from the technology.

Proliferating scams

Researchers and technologists across the public and private sectors are racing to create new tools to reliably identify when a piece of media has been synthetically manipulated.

For example, the ability to “clone” voice audio and mimic individuals has quickly become a standard tool for fraudsters to bilk unsuspecting victims over the phone. The Federal Trade Commission recently announced a voice-cloning challenge, canvassing the public for technical solutions that can detect cloned voices in real time or after the fact.

At a meeting last November, Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., explained how a staff member’s spouse had received a phone call from scammers using voice-cloning technology to imitate the “panicked voice” of their son serving overseas in the U.S. military. While the call’s recipient deduced that the voice was not genuine, Klobuchar wondered if the result would have been the same if the scammers had called the man’s grandparents instead.

Thousands of people receive these calls every year, and the bar for voice cloning is absurdly low: Experts have told Congress that malicious actors need only a few minutes of audio to copy a person’s voice.

Voice cloning is already showing up in political dirty tricks. On Jan. 22, one day before the New Hampshire presidential primary, the state's attorney general reported multiple complaints about a robocall purporting to come from President Joe Biden urging voters to avoid casting a primary ballot. The AI-generated message tells voters, "Your vote makes a difference in November, not this Tuesday.”

Rep. Brittany Pettersen, D-Colo., has sponsored a bill that would set up a federal task force to examine how deepfakes could disrupt the financial services sector and threaten consumers with more convincing scams and fraud.

“The financial sector knows that this is front and center on what they need to deal with across the board to protect consumers and businesses,” Pettersen said in an interview. “What we need to be worried about in Congress is protecting our economy and some of the enormous fallout … that could come if we’re not implementing technologies for prevention.”

Older Americans are particularly vulnerable to phone-related scams. At a recent event in Washington, D.C., Rohit Chopra, head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, said he wondered whether society is “ever going to be able to get some of the genie back into bottles, particularly when it comes to how much fraud [there] can be” with tools like voice cloning.

“That’s something we think about: the way in which you can copy a grandchild’s voice, go to their grandparents with diminished capacity and take their life savings,” Chopra said. "I think this is like a different type of warfare and a different type of human interaction.”

A race for detection tools

Section 4.5 of the White House AI executive order directs the Commerce Department to lead a process exploring how to reduce risks associated with AI-generated content. In particular, the order tells Commerce to report on existing tools like digital watermarking and the potential for developing new technologies to identify synthetically manipulated media.

Watermarking involves embedding digital markers within an algorithm. These markers show up in any photos, videos or text the algorithm generates, leaving signals that outside parties can use to verify authenticity or confirm digital manipulation.

The Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity — a group created and managed by Adobe, Intel, Microsoft, the BBC, Sony and other companies — is working to develop and spread a set of new open, interoperable technical standards for many forms of digital media. Those standards would use a new process that attaches a traceable history for each piece of media at the file level. A master file is then kept in a local or cloud-based storage system for comparison, giving consumers hard answers around when an image or video file was created, by whom and whether any pixels were altered along the way.

However, experts warn that watermarking technologies would be effective only for algorithms that chose to adopt them. These tools may be helpful in authenticating government communications to the public or content created by firms that want to play by the rules, but it would require widespread voluntary adoption by AI system owners — including bad actors — to serve as a real check on malicious deepfakes.

Meanwhile, federal agencies are pouring millions of dollars into building new technologies that can examine different forms of media and determine whether they have been altered or created by a machine. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has spent more than $100 million on a pair of research projects that seek to detect and defend against deepfakes in different ways.

Semantic Forensics focuses on how it's possible to detect errors in generative AI outputs, including deepfake video, audio and imagery. It combines machine learning with human-based analytics to detect deepfakes at higher rates than currently available commercial models do.

That research is among the building blocks for projects like RED, another DARPA project that aims to reverse-engineer deceptive media and capture digital signatures that can be traced back to the specific algorithms, large language models and training data sets used to create them. In theory, such technology could reveal not just whether a piece of media is synthetic, but who made it and what tools were used.

Will Corvey, a program manager at DARPA, told Nextgov/FCW that apart from providing technical tools for researchers, Semantic Forensics is meant to be “intuitive and broadly accessible” to the less-technical public. It could be used to build biometric models for “persons of interest” — public figures and others who have hours of video and audio recording on the internet and are thus prime targets for deepfakes. SemaFor uses that media to study facial movements, musculature, head tilts and voice features unique to those individuals in order to help authenticate videos they appear in.

“For people who might not be familiar with the underlying forensics,” Corvey said, “it’s giving you dots of the face that basically provide explainable features that I can then use to look at a video and I see, ‘Here is where the computer thought this was quite different than what was expected,’ even if it’s a pretty good deepfake video.”

Evolving threat

To date, however, none of these public- or private-sector tools can say with certainty whether a piece of media has been manipulated. The best they can offer is a probability estimate. In a 2019 Facebook contest that drew more than 2,000 participants and led to 35,000 unique methods to detect deepfake videos, the most promising models were successful just 82% of the time when used on a training set provided by Facebook. That accuracy dropped to 65% when used on brand-new deepfakes.

Further, the tools developed by DARPA and others rely on the same underlying machine-learning algorithms that are used to generate deepfakes. This creates a perpetual cat-and-mouse dynamic, where bad actors can study detection algorithms to learn how to make more convincing imitations in the future.

The National Science Foundation has doled out millions in grant funding to develop better tools to detect deepfakes. But any benefits from those tools will degrade over time without continued vigilance and improvements. That means this technological war will continue for the foreseeable future.

“One thing to understand is this deep fake technology is moving at a rapid pace. That means the countermeasures also have to move at a rapid pace,” said Dr. Nina Amla, a senior science advisor at the NSF. “This is not something where you say, ‘We detected this deepfake, we’re done.’ No, because they’re going to keep evolving and there’s a lot of money in this area” for cybercriminals.

This article originally ran in the January/February issue of Nextgov/FCW magazine. Derek B. Johnson is former FCW staff writer who currently reports on cybersecurity at Cyberscoop.

NEXT STORY: FBI disrupts botnet controlled by Russian security services