The Founding Fathers Encrypted Secret Messages, Too

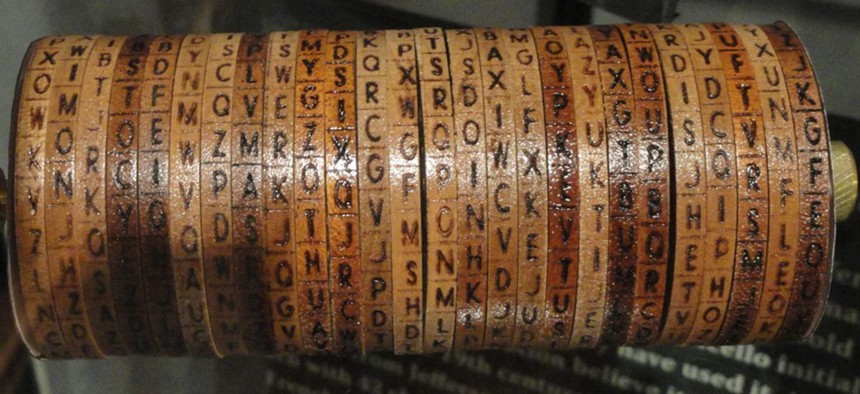

A replica of a Jefferson cylinder cipher at the National Cryptologic Museum Wikimedia Commons

Centuries before cybersecurity, statesmen around the world communicated with their own elaborate codes and ciphers.

Thomas Jefferson is known for a lot of things—writing the Declaration of Independence, founding the University of Virginia, owning hundreds of slaves despite believing in the equality of men—but his place as the “Father of American Cryptography” is not one of them.

As a youth in the Virginia colony, Jefferson encrypted letters to a confidante about the woman he loved. While serving as the third president of the newly formed United States, he tried to institute an impossibly difficult cipher for communications about the Louisiana Purchase. He even designed an intricate mechanical system for coding text that was more than a century ahead of its time.

Cryptography was no parlor game for the idle classes, but a serious business for revolutionary-era statesmen who, like today’s politicians and spies, needed to conduct their business using secure messaging. Codes and ciphers involving rearranged letters, number substitutions, and other now-quaint methods were the WhatsApp, Signal, and PGP keys of the era.

Going into the Revolution, Americans were at a huge disadvantage to the European powers when it came to cryptography, many of which had been using “black chambers”—secret offices where sensitive letters were opened and deciphered by public officials—for centuries. It was not uncommon for the messages of Revolutionary leaders and, later, American diplomats in Europe, to be intercepted and read by their enemies, both at home and abroad.

As a result, early Americans “operated in multiple secret languages during the Revolution,” says Sara Georgini, the series editor of The Papers of John Adams, at the Massachusetts Historical Society. “They didn’t throw away those habits once the new nation got formed.” The Founding Fathers continued to rely on encryption throughout their careers: George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, John Jay, and James Madison all made ample use of codes and ciphers to keep their communiqués from falling into the wrong hands.

But no one went as deep into the encryption game as Jefferson. Born in 1743 in Shadwell, Virginia, Jefferson was learning Latin, Greek, and French by the age of 9. He went to the College of William & Mary at 16, to study physics, math, and philosophy, and by early 1764, Jefferson, then 20 years old, was writing letters in code. At first glance, a cryptic letter he sent that year to John Page, a close college classmate, is difficult to parse: It drops Latin phrases in the middle of what sound like emotional ultimatums about an upcoming contractual agreement with some man, whose name is written in Greek characters.

“My fate depends on αδνιλεβ’s present resolutions: by them I must stand or fall,” Jefferson writes. But the Greek characters are in fact an anagram for Rebecca Burwell, a 17-year-old from Yorktown he wanted to marry. Four days later, Jefferson decided that his earlier code was too obvious. “We must fall on some scheme of communicating our thoughts to each other, which shall be totally unintelligible to every one but to ourselves,” he told Page.

Although most encrypted letters were a mixture of cipher and “plaintext,” deciphering them could be a patience-straining process. It was easy to mess up during the encoding or decoding process. Letters using dictionary and book codes—where the writer provided a set of numbers that indicated the page, column, and position where the word they wanted could be found in an agreed-upon book—could become garbled by line-counting errors.

The alternative was having secrets stolen and—then as now—even leaked in an embarrassing scandal. As some of the colonists grew more radical following the Boston Massacre, a cache of private letters by Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson and his lieutenant were leaked and published in newspapers up and down the Eastern Seaboard. In the letters, Hutchinson said that colonial Americans were owed only a fraction of the rights English citizens could expect. Americans took to the streets to burn effigies of the two men.

On Christmas Day in 1773 none other than Benjamin Franklin copped to being the source of the leak, a sort of colonial Julian Assange. He lost his job as deputy Postmaster General of North America, but things accelerated quickly toward revolution and war, raising the stakes for secret communications even higher. Soon, similarly compromising documents emerged from the offices of colonial governors in New York, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina—duly stolen and leaked to newspapers.

During the Revolutionary War, American leaders had “an informal and amateur approach to espionage,” says Georgini. Some relied on dictionary codes. George Washington, a code enthusiast himself, used an invisible-ink formula devised by John Jay to communicate with the members of his spy cell, the Culper Ring, in British-controlled New York City. “If deciphered, the British could identify the senders, arrest them, and hang them,” says Alexander Rose, the author of the book Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring (now a TV series, Turn: Washington’s Spies).

Even after the war was finished, Washington remained suspicious of sending letters by mail. “By passing through the Post offices [my sentiments] should become known to all the world,” he complained in a 1788 letter to Marquis de Lafayette.

As the newly formed United States entered the world of diplomacy, invisible ink and book codes were no longer going to cut it. Forced to hold its own against sophisticated European players, American cryptography evolved in tandem with U.S. diplomacy, explains Georgini. Its foreign ministers communicated in a riot of different secret methods, and the deluge of codes and ciphers sailing across the Atlantic was a chaotic assemblage of individualized systems. The diplomatic corps in Europe generally relied on variations of the clunky, medieval-era nomenclator system, which saw statesmen lugging around long code lists, where hundreds or thousands of words and syllables—from “a” to “Amsterdam” or “Aaron Burr”—were reassigned as combinations of digits. Still, it is estimated that more than half of all U.S. foreign correspondence ended up in British hands.

Back on U.S. soil, domestic surveillance was still a major concern heading into the 19th century. “The infidelities of the post office and the circumstances of the times are against my writing fully & freely,” Jefferson concluded in 1798, when he was vice president. His concern, says James McClure, the general editor of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson at Princeton, “was the opposition getting a hold of something he wrote: They would put it in the newspapers and use it against him.” But even writing in code was not a failsafe. Jefferson understood that the popular nomenclator system was vulnerable to security breaches; all it took was a code list falling into the enemy’s possession. So he decided to go a step further. “Jefferson got interested in encipherment systems that didn’t rely on lists,” says McClure.

Sometime in the 1790s, Jefferson designed a “wheel cipher,” which was “so far ahead of its time, and so much in the spirit of the later inventions, that it deserves to be classed with them,” writes David Kahn in his seminal cryptography book, The Codebreakers. Jefferson’s device, which included 36 turning wooden wheels with the letters of the alphabet marked on their edges, was remarkably similar to a device the U.S. Army adopted more than a century later, in 1922.

“Had the President recommended his own system to Secretary of State James Madison, he would have endowed his country with a method of secret communication that would almost certainly have withstood any cryptanalytic attack of those days,” Kahn writes. “Instead he appears to have filed and forgotten it.”

Many of the other methods that Jefferson was most enthusiastic about, such as the “perfect cypher,” designed for him by the mathematician Robert Patterson, just never caught on. As with privacy-minded people trying to get their friends to use PGP keys today, sometimes the newfangled inventions felt like too much trouble. Jefferson’s U.S. minister in Paris, Robert Livingston, simply refused to use Patterson’s complicated transposition cipher—where plaintext is reordered and transformed—while negotiating the Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson developed a specialized non-list cipher to be used by Meriwether Lewis for his expedition into the Louisiana territory that hinged on the keywords “antipodes” and “artichoke.” Lewis did not appear to share the president’s enthusiasm, or was just too tired from crossing the continent on boat, foot, and horseback. He never ended up using it.

The best method of keeping encrypted messages completely secure appears to have been losing or destroying the translation key. To this day, scholars are still working to piece together decoded passages in diplomatic letters from the revolutionary generation. “There are at least three codes for which no key has been found,” says McClure.

A couple of years ago, a cryptographer at Princeton finally managed to crack Patterson’s supposedly “indecipherable” code. It turns out, an encoded block of text that Patterson sent to Jefferson in 1801 as an example of an unbreakable code was the Declaration of Independence.