Should Libraries Be the Keepers of Their Cities’ Public Data?

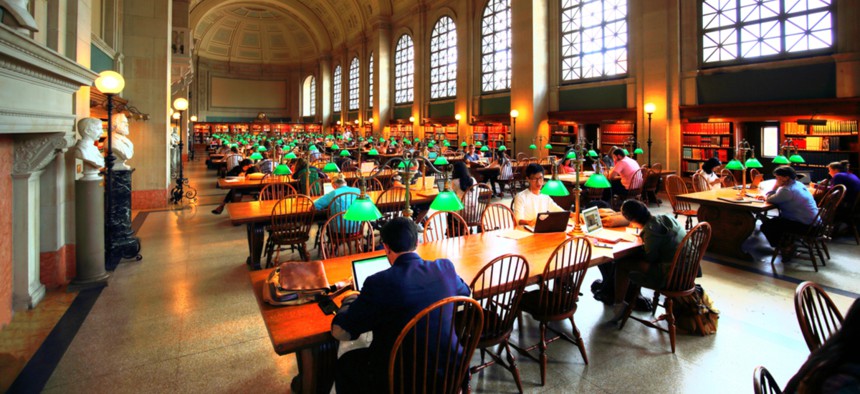

Patrons at a public library in Boston. Elijah Lovkoff/Shutterstock.com

Public libraries are one of the most trusted institutions, and they want to make sure everyone has access to the information cities are collecting and sharing.

In recent years, dozens of U.S. cities have released pools of public data. It’s an effort to improve transparency and drive innovation, and done well, it can succeed at both: Governments, nonprofits, and app developers alike have eagerly gobbled up that data, hoping to improve everything from road conditions to air quality to food delivery.

But what often gets lost in the conversation is the idea of how public data should be collected, managed, and disseminated so that it serves everyone—rather than just a few residents—and so that people’s privacy and data rights are protected. That’s where librarians come in.

“As far as how private and public data should be handled, there isn’t really a strong model out there,” says Curtis Rogers, communications director for the Urban Library Council (ULC), an association of leading libraries across North America. “So to have the library as the local institution that is the most trusted, and to give them that responsibility, is a whole new paradigm for how data could be handled in a local government.”

In fact, librarians have long been advocates of digital inclusion and literacy. That’s why, last month, ULC launched a new initiative to give public libraries a leading role in a future with artificial intelligence. They kicked it off with a working group meeting in Washington, D.C., where representatives from libraries in cities like Baltimore, Toronto, Toledo, and Milwaukee met to exchange ideas on how to achieve that through education and by taking on a larger role in data governance.

It’s a broad initiative, and Rogers says they are still in the beginning stages of determining what that role will ultimately look like. But the group will discuss how data should be organized and managed, hash out the potential risks of artificial intelligence, and eventually develop a field-wide framework for how libraries can help drive equitable public data policies in cities.

Already, individual libraries are involved with their city’s data. Chattanooga Public Library (which wasn’t part of the working group, but is a member of ULC) began hosting the city’s open data portal in 2014, turning a traditionally print-centered institution into a community data hub. Since then, the portal has added more than 280 data sets and garnered hundreds of thousands of page views, according to a report for the 2018 fiscal year.

Under a Knight Foundation-funded initiative called Open Data to Open Knowledge, Boston partnered with its public library to revamp the city’s open data program in 2015 with the goal of driving engagement between the public and the city’s data. The library, which is part of ULC’s working group, ultimately helped catalogue Boston’s trove of existing data into a user-friendly portal. In doing so, they made clear that the data is part of the public domain, with no restrictions to access.

It’s a fitting task for libraries, whose mission has always been to “collect and make accessible to the public information that the public has rights to read,” says open data advocate Alex Howard. “That’s their job.”

To ensure that data is truly equitable, ULC’s initiative will emphasize education. That is, helping residents understand how their data is being used by governments and private entities—as well as the implications of those uses—and become knowledgeable about their privacy and data rights.

Public libraries already provide resources like computer training, tech support, and job preparation. So to Pam Ryan, director of service development and innovation at Toronto Public Library, teaching data literacy is an obvious next step.“Public libraries are the first defender of digital privacy; we have expertise in data policies and information management, and we have long played that role in city building,” she says.

Though Canada’s data privacy laws differ from the U.S.’s, the Toronto Public Library gives the rest of ULC’s working group a model for what educational programs can look like. In 2016, it launched its Digital Privacy Initiative, inviting speakers from civil liberty associations and academic research labs to give talks on everything from surveillance threats to privacy law. “For the next step, in 2019, we’re talking about algorithmic literacy programming,” Ryan says. “So what does it mean when you’re searching things? And what does it mean when those brown boots [that you searched for once] follow you around the internet?”

The Toronto Public Library is also in a unique position because it may soon sit inside one of North America’s “smartest” cities. Last month, the city’s board of trade published a 17-page report titled “BiblioTech,” calling for the library to oversee data governance for all smart city projects.

It’s a grand example of just how big the potential is for public libraries. Ryan says the proposal remains just that at the moment, and there are no details yet on what such a model would even look like. She adds that they were not involved in drafting the proposal, and were only asked to provide feedback. But the library is willing to entertain the idea.

Such ambitions would be a large undertaking in the U.S., however, especially for smaller libraries that are already understaffed and under-resourced. According to ULC’s survey of its members, only 23 percent of respondents said they have a staff person designated as the AI lead. A little over a quarter said they even have AI-related educational programming, and just 15 percent report being part of any local or national initiative.

Debbie Rabina, a professor of library science at Pratt Institute in New York, also cautions that putting libraries in charge of data governance has to be carefully thought out. It’s one thing for libraries to teach data literacy and privacy, and to help cities disseminate data. But to go further than that—to have libraries collecting and owning data and to have them assessing who can and can’t use the data—can lead to ethical conflicts and unintended consequences that could erode the public’s trust.

Libraries are committed to protecting patrons’ data—in fact, Rabina says it’s strongly emphasized in library science education—and they often delete records of searches. But what does it mean for the library’s commitment to their patrons when they are pressured into entering public-private partnerships with companies that think differently about consumers’ data? That’s just one of the many questions workgroups like ULC’s will have to think through.

Rabina says libraries would need major support. Not only in funding and skills, but also support for having autonomy over the decisions they make with the data.

“We can start moving forward, and with a lot of caution and attention to where we’re becoming not librarians anymore in our mission,” she says. “You know, our job is not to manage data for the city. Our job is to collect, organize, and provide access to information for the public.”