How a Tiny Website Became the Police's Go-To Genealogy Database

CI Photos/Shutterstock.com

“I never expected anything like this.”

Ever since investigators revealed that a genealogy website led police to arrest a man as California’s notorious Golden State Killer, interest in using genealogy to solve crimes has exploded. DNA from more than 100 crime scenes has been uploaded to the same genealogy site. A second man, linked to a double murder in Washington state, has been arrested. This is likely only the beginning.

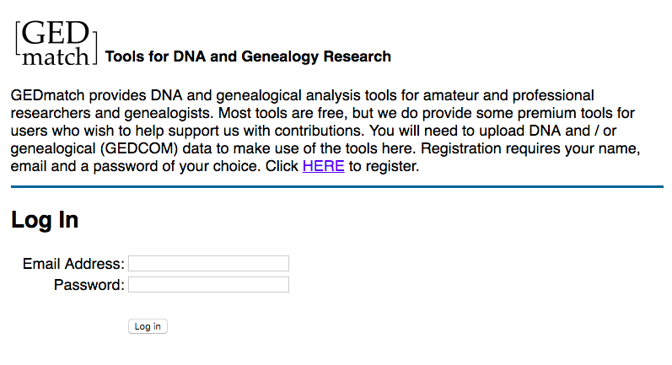

At the center of all this is GEDmatch—a free genealogy website run by just two men who live 1,000 miles apart, an engineer in his 60s who lives in Texas and a 79-year-old retired businessman turned professional guardian in Florida. The site is—or was—a side project for them.

“I never expected anything like this,” says Curtis Rogers, who started GEDmatch along with John Olson. Rogers, who lives in Florida, had no idea investigators were using GEDmatch to find criminals until he saw the news about the Golden State Killer. “My initial reaction was I was upset,” he says. “I didn’t like this use of our website.”

To track down the suspect, investigators had created a fake profile on GEDmatch and uploaded DNA from a 1980 crime scene, where it matched a distant relative of the man eventually arrested. The weeks after the news hit were a scramble for Rogers: to update GEDmatch’s terms of service, to alert users that law enforcement was searching site, and most of all, to sort out his own complicated feelings on the subject.

Some users concerned about privacy did delete their data from GEDmatch, Rogers says. But he’s gotten an “awful lot” of emails thanking him, too. One in particular haunted him. He says a woman wrote that her father was a serial killer, and she wanted her data out there to give the families of his victim’s closure.

“What is the right thing to do? I’m still not sure,” he says. “I think the best thing we can do is admit what we are open and honest.” The site’s terms of service now explicitly tells users that “DNA obtained and authorized by law enforcement” can be uploaded to identify a perpetrator of a “violent crime.”

Law enforcement already has a national DNA database of its own of course—codis, or the Combined DNA Index System. But the type of genetic information in codis is more limited and thus less useful for finding relatives than that on GEDmatch. By using GEDmatch, police have radically expanded the power of their DNA searches. A small website with no full-time staff has become the DNA and genealogy database for American police.

GEDmatch grew out of Rogers’ own interest in genealogy, which began as a teenager. On vacations, he would visit cemeteries and courthouse to track down records of relatives. And when he got on the genealogy website Family Tree DNA, he became manager of the Rogers surname project, one of the site’s many such genealogy research groups. Through that, he met new relatives matched via DNA and spent hours emailing back and forth trying to find out where their family trees overlapped. A computer program, he thought, could compare family trees much faster. Someone recommended John Olson as a guy with the technical chops to write the program, so Rogers reached out. Olson’s program worked beautifully.

“I said, this is much too good for just the Rogers surname project,” recalls Rogers. “Let’s put it out there for people to use these tools, and we wanted it to be free to other people.” In 2010, he registered the domain GEDmatch.com, which comes from GEDCOM, the file format for family trees originally developed by the Mormon Church. The site grew through word of mouth.

As users requested more sophisticated features, Olson and Rogers added them. Today, GEDmatch allows users to upload raw DNA data from consumer genetic testing companies like 23andMe and Ancestry to compare with each other. It also offers granular tools that, for example, let users find matches along one particular segment of a chromosome. Genetic genealogy—the use of DNA to build family trees—has been described to me as a “citizen science,” in which the tools are freely shared. GEDmatch is the paramount example.

The site now has about a million users, according to Rogers. It still looks like something from the 1990s. The basic site is free, but to defray the $200,000 a year in server costs, it also offers $10 a month membership with access to premium tools.

Over time, GEDmatch has become the go-to destination for serious genetic genealogists. People have found distant family members on the site, adoptees have found their biological parents, donor-conceived kids have found their sperm donors. It’s no wonder the police came calling, too.

When the FBI created codis in the 1990s, the way to identify people by DNA was looking for short tandem repeats, or STRs. As their name implies, these are short sequences that can be repeated dozens or hundreds of times in the genome. The number of repeats is highly variable from person to person. STRs are not genes, though, and they reveal little about the appearance or medical conditions of a person, sidestepping some of the privacy concerns of police collecting DNA. Today, codis contains STR profiles of over 16 million offenders and arrestees. Each profile looks for STRs in up to 20 locations in the human genome.

In contrast, the DNA profiles on GEDmatch contains information at some 600,000 or so locations in the genome. These profiles come from customers who’ve tested with commercial companies like Ancestry and 23andMe, which identify the genetic letters that appear in those 600,000 locations by looking for SNPs, or single-nucleotide polymorphisms. SNPs are not as variable as STRs, but you can test a lot more of them. They can also be in the middle of genes; that is how 23andMe tells you if you have a certain breast-cancer gene variant. And with enough SNPs, you can use it to trace the geographic origins of ancestors and find distant relatives.

Recently, law enforcement has gotten interested in using SNPs for leads in cold cases. Forensics labs are validating tests for SNPs that can reveal general information about geographic ancestry or physical traits like eye and skin color. But this work—cutting-edge by forensics standards—only looks at a few dozen to a couple hundred SNPs compared to the 600,000 of consumer DNA tests.

Forensics has been slow to adopt recent advances in genomics—for good reason, given the high stakes of a criminal case. But it does mean that genetic genealogists who use DNA to find family members on GEDmatch are far ahead of forensics labs.

“Law enforcement continues to use outdated DNA databases, and I don’t see a movement toward using better DNA databases,” says Blaine Bettinger, a genealogist and lawyer affiliated with GEDmatch. Bettinger says he would prefer that police build their own SNP database, where searches can be appropriately regulated. Right now, there is essentially no oversight on when and how police use GEDmatch, which is, after all, a public database open to anyone. (In contrast, using CODIS to look for close family members is regulated state by state, and many do not allow it at all.)

It’s hard to argue against using a genealogy site to catch a serial killer and rapist like the Golden State Killer. But what about less serious crimes, like drug offenses, asks Bettinger. “I think that’s just overreach,” he says. “That makes me uncomfortable. We leave DNA everywhere we go. Everywhere we touch has DNA. There’s got to be a limit.” GEDmatch’s terms of service tries to limit law enforcement use to “violent crimes” defined as homicide or sexual assault, though the site as no way of verifying that.

For now, money is a real limiting factor. STR testing is relatively cheap; SNP testing is not. “The methods we have now in crime labs are very cost-effective, meaning you can generate a DNA profile in a relatively short amount of time at low cost from very low amounts of DNA,” says Daniele Podini, a forensics expert at George Washington University who studies the use of SNPs in forensics. Parabon Nanolabs, the forensics company that recently uploaded DNA from 100 crime scenes to GEDmatch, charges law enforcement agencies $1,500 in lab fees plus $2,250 for its genetic-genealogy work.

SNPs, unlike STRs, also reveal an awful lot about a person’s appearance and health information, raising a whole new set of possible privacy concerns about the information police are gathering when they collect DNA. And the methods for finding distant relatives through SNPs and genealogy have not been formally validated in a forensics lab. (In both the California and Washington cases, the suspects’ DNA was collected surreptitiously and matched using STR to crime scene DNA to confirm the genetic-genealogy work.) Many issues, technical and social, still to be worked out.

“People on GEDmatch are part of an experiment,” says genealogist Debbie Kennett. “And the experiment is taking place on GEDmatch.”