Working the crowd: How USAID leveraged free labor to map a loan program’s effectiveness

USAID

Data project provided key insights.

The crowd can be a great source of free labor, as long as you’ve done most of the hard work in advance and you’ve given those volunteers a good reason to participate, officials from the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Geocenter said Thursday.

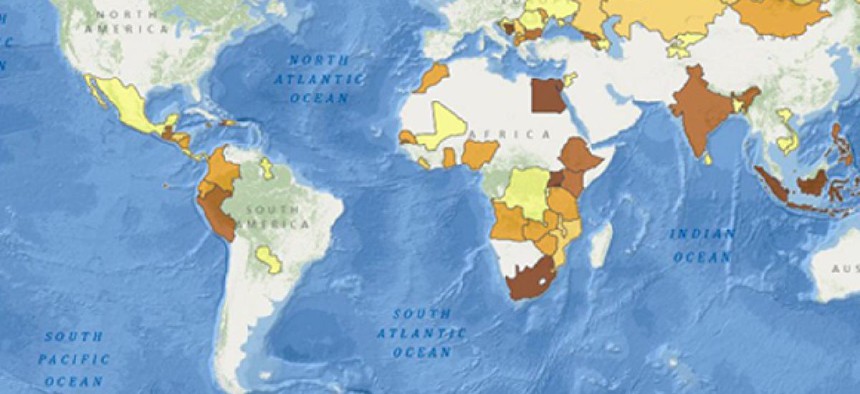

The Geocenter recently tapped 145 volunteers to help pull together a map of loans to entrepreneurs in developing countries backed by USAID’s Development Credit Authority.

The resulting map will give DCA and in-country lenders a better idea of where their loans are going and how effectively they’re meeting key priorities such as alleviating rural poverty, USAID communications specialist Stephanie Grosser said. Other organizations also could draw new conclusions from the maps, she said, for instance by laying maps of poverty rates, agriculture yields and small business startup rates on top of them.

USAID sought help from the volunteers for the mapping project because the original data -- collected from lenders across the world -- contained a mix of information in the location column that made mapping problematic. The agency needed to standardize that information to the equivalent of a state-level designation, Grosser said, but didn’t have the time to do it in-house or the money to hire a contractor.

Other agencies have turned to crowds for even more daunting tasks such as a the National Archives and Records Administration’s project to transcribe many of its documents.

Once USAID settled on crowdsourcing as its model, most of the heavy lifting was still ahead said Grosser and Shadrock Roberts, Geocenter’s senior spatial analyst. The pair were speaking at a discussion sponsored by the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Science and Technology Innovation Program.

First, they had to strip the data of personally identifiable information such as the loan recipients’ names, business names and addresses, Grosser said. They also had to spend hours with their general counsel ensuring the initiative wasn’t putting USAID in any legal jeopardy, such as being sued by volunteer mappers who expected payment. And they had to find a platform for the crowdsourcing, in this case a retrofitted page from Data.gov, the government’s public information repository.

Finally, the agency had to find a crowd.

In this case, they started by reaching out to two organizations: Standby Task Force, a group of crowdsourcing volunteers, and GISCorps, an organization for professional mappers. They also reached out to the public at large through social media, including nonmappers who were fans of USAID’s foreign development mission.

The general public made up about 40 percent of people who participated in the project, according to a case study report.

Roberts and Grosser opted to lump all the mapping into a single weekend. Their goal was partly to leave the raw data up for as short a period as possible on the advice of their general counsel, they said. They also wanted to increase the sense of community and excitement among the volunteers, Grosser said, including by inviting Washington-based volunteers to come work round-the-clock at the USAID innovation center.

In the end, the program was more successful than they expected. All the mapping was done in 16 hours rather than the allotted 60 hours and people who logged onto the site Saturday morning were left with nothing to do.

One lesson, Roberts said, is that a surprising number of tasks can yield a crowd that’s enthusiastic about either the task or the agency sponsoring it.

“I found this task to be appallingly unsexy,” Roberts said, “but everyone came out in droves for it anyway and they did a really good job.”

NEXT STORY: FedBizOpps contractor under FBI investigation