sponsor content What's this?

Assets in the Air Provide High-Value Data for Feds

Presented by

FedTech

Agencies use drones to gather information, but must figure out how to manage the ever-growing mountains of data they collect.

Alisa Coffin, a research ecologist with the Agriculture Department’s Agricultural Research Service(ARS), anticipated that she’d need more infrastructure when she used a drone to assist with her crop production studies in Georgia.

“We knew there was going to be a lot of data to handle, and we knew we would have high processing needs,” she says.

The DJI drone helped her and her team gather high-resolution, multispectral images that she hopes will give them better insight into the density and health of the crops below.

“The drone data provides an important connection between what we’re collecting on the ground and what we can see with satellite imagery,” she says. “You need a middle step.”

Drones are increasingly popular across the federal government, with the military services and agencies such as the Interior Department and the Forest Service all using or testing unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs.

Shawn McCarthy, research director for the Government Insights group at IDC, notes that the ease of data collection enabled by drones can present both benefits and challenges.

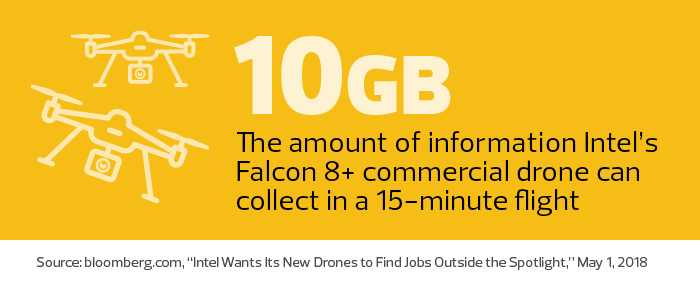

“There is a substantial geographic information system element in drone data collection, along with video,” McCarthy says. “It’s not that either of those elements is new, but drones help access data in an efficient and inexpensive manner, which leads to a greater amount of data to deal with.”

Processing Drone Data Takes Time and Computing Horsepower

Robert Wells, a research hydraulic engineer with ARS, flew a drone over fields in Minnesota and Iowa last summer, collecting data to help farmers better manage soil erosion.

Using the unmanned aerial vehicle, Wells gathered images that provided 3.5 billion data points from a single field within three hours.

Alisa Coffin uses a DJI drone to collect data for her USDA research, and has upgraded her storage capacity to handle the extra information.

But even with the help of a 24-core workstation, it took him an entire week to process the data from each field and 18 weeks to process the data for the entire project. “It’s amazing how much data was generated in that short period of time. I have multiterabyte hard drives, and I started filling them up quickly,” Wells says. “If I weren’t working solo — if multiple people were doing this every single day — the storage requirements would be devastating.”

Coffin’s office made investments to handle the new workload triggered by the use of the DJI drone: a rack-mounted PC solution with 256 gigabytes of RAM dedicated to processing drone images, including components such as a Dell Precision Rack 7910, a Dual Intel Xeon 6 Core Processor E5-2643 v4 and an NVIDIA Quadro K6000 12GB video card.

The solution provides more than 7TB of storage capacity, but Coffin expects to create 2TB to 3TB of new data, largely images, this summer alone. “It’s starting to fill up,” she says.

She finds drone-gathered data so helpful that she has also acquired a Matrice M210 drone to gather thermal infrared imagery and an inexpensive consumer drone to collect additional photos. However, she always “strongly cautions” others who are interested in dabbling with drones.

“They look so simple, and the results look so promising,” Coffin says. “But if you haven’t thought through all of the components of a UAV program — the software, the hardware, the people — you can end up wasting a lot of time and money and not have the quality of data you need to do the research.”

The Cloud May Ease Data Storage Concerns

In the fall of 2017, U.S. Customs and Border Protection tested UAVs to determine whether they could assist with the agency’s mission. While drones show promise for gathering data at the border, the agency faces challenges in storing, processing and securing that data, says Tom Mills, chief systems engineer in the department’s Office of Information and Technology.

“I think we’re still in that stage of assessing,” Mills says. “We face an issue with the logistics of transmission and where it’s stored. We also have to figure out how to store the sheer amount of data and how to process that data.”

For the latter issue, the cloud may provide an answer. Mills notes that the price of data storage is falling and that cloud solutions provide flexibility. “The good thing about the cloud is, it’s elastic,” he says. “As soon as we don’t need it, we’re not paying for it.”

The Coast Guard has decided that a drone is worth the effort. The Stratton, a 418-foot national security cutter with a crew of about 150, has carried a drone on board for the past 18 months.

“It’s performing well for us,” says Capt. Craig Wieschhorster, the vessel’s commanding officer. “It gives us a tactical advantage.”

The drone helps the crew conduct fisheries enforcement, flying over closed areas to see if anyone is fishing illegally. It also assists in counterdrug operations, allowing the Coast Guard to gather intelligence and assess situations before intercepting vessels suspected of trafficking drugs.

“We’re able to see everything these guys are doing, without them seeing us,” Wieschhorster says.

When it comes to one of the Coast Guard’s classic missions — search and rescue — pilots can look at images collected by the drone “before even getting in the helicopter,” he says. That lets them reduce the amount of potentially dangerous time surveying conditions from the air.

More Drones Leads to More Data for Navy

The Navy is currently preparing to move on from smaller UAVs to a larger, unmanned surveillance aircraft currently under development. Christopher Page, command information officer for the Office of Naval Intelligence, says that the service’s drone program — coupled with data from a growing array of other sensors and sources — is leading to “significant, near-term increases in the volume, variety and velocity of data.”

To accommodate the influx, Page says, the Navy will increasingly treat data storage and processing as an ongoing operational expense, rather than as a one-time capital outlay.

“The Navy is not going to generate the necessary capabilities and capacities through the traditional approach of making large, capital-intensive investments in on-premises hardware, software and support,” Page says. “It is, instead, going to generate what it needs by embracing an operations-intensive, cloud-first approach that emphasizes taking full and effective advantage of commercial cloud services.”

On a much smaller scale, USDA’s Wells is looking for better solutions to store and process the data he collects in the fields of the Midwest. He is hoping that cloud resources might provide those functions, and also allow him to quickly share large data sets with his colleagues across the country.

“The technology itself is absolutely glorious,” Wells says. “I intend to do a great deal more of this, but I’m trying to find an easier path forward.”

This content is made possible by FedTech. The editorial staff of Nextgov was not involved in its preparation.