L.A.’s Public Earthquake-Warning App Is the First in the U.S.

ShakeAlertLA aims to give smartphone users a few seconds’ warning of imminent quakes.

On January 3, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced the release of ShakeAlertLA, a new earthquake-warning app for residents of Los Angeles County. The app—the first of its kind in the United States—promises to “save lives by giving precious seconds to you and to your family to take action and to protect yourselves,” Garcetti told reporters at a launch event at City Hall.

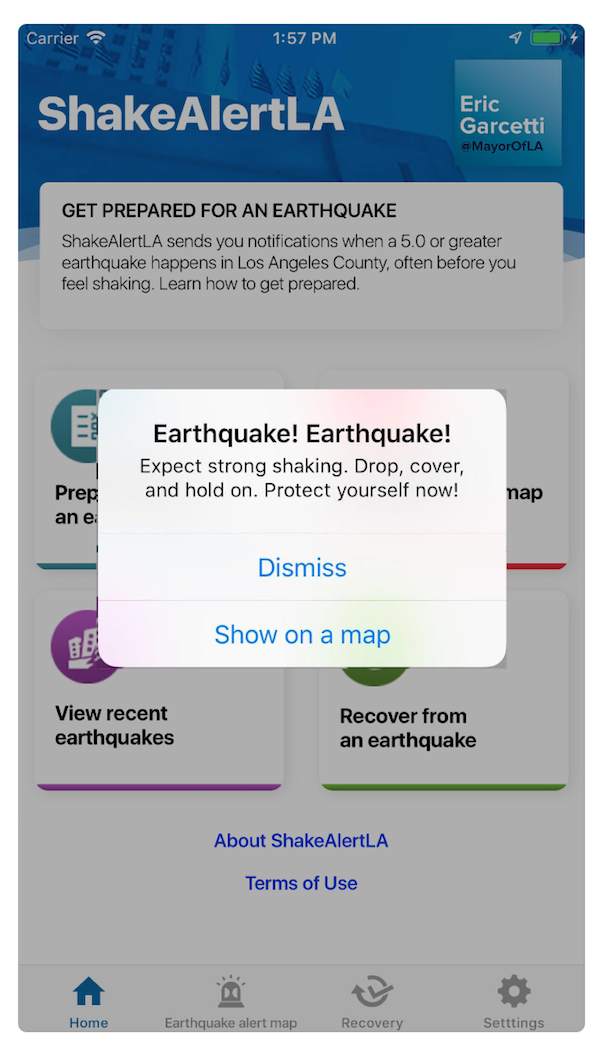

Available to download in both English and Spanish in the Apple and Google Play stores, ShakeAlertLA is designed to give smartphone users a warning, with sound, of earthquakes of 5.0 magnitude or larger, a few seconds or more before the shaking begins. That’s not a lot of time, but even a brief window can be enough to gather family members and “drop, cover, and hold on,” as earthquake drills instruct.

ShakeAlertLA was developed by the City of Los Angeles with the U.S. Geological Survey, AT&T, and the Annenberg Foundation. It grew out of the USGS’s larger ShakeAlert project for the West Coast, which has been under way since 2006 but delayed by federal funding cuts. Although ShakeAlertLA only works in L.A. County, the technology is open source, so other municipalities and developers can use it to make their own apps. (A separate USGS-partnered app called QuakeAlert, developed by the tech firm Early Warning Labs, is already available in beta.)

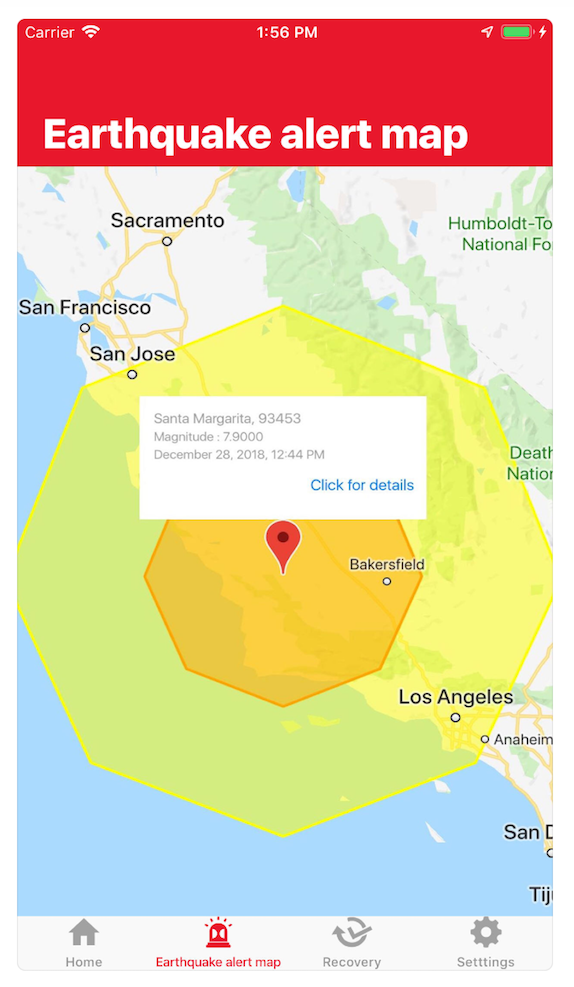

The new app depends on hundreds of sensors that collect data around geologic faults. When the sensors detect strong enough seismic activity, a notification is pushed out to users’ phones. The farther that app users are from the quake’s epicenter, the more advance warning they are likely to receive. Those very close to the epicenter may not be alerted until the shaking has already begun.

The city described the release as a pilot, and dozens of early users left reviews complaining that the iPhone app crashed. A city representative said on January 4 that the city was working to debug the app and would release updates shortly.

Devising an effective early-warning system for earthquake-vulnerable cities has long been a huge public-safety challenge. Seismic waves travel at speeds of kilometers per second. The ubiquity of smartphones offers an opportunity to instantly reach millions of people at once, but even if the app is running smoothly, it’s not a perfect solution: Notifications can’t reach people whose smartphones are turned off, set to silent, or not charged. And those without smartphones are left out entirely.

Mexico and Japan adopted earthquake early-warning systems years ago, but they are still imperfect (both have issued false alarms). On September 7, 2017, when an 8.2-magnitude earthquake hit off Mexico’s southern coast, Mexico City residents got about 90 seconds of warning. But a couple of weeks later, on September 19, they did not receive an alert of a 7.1 quake until after the shaking had started, because its epicenter was much closer.

American scientists who interviewed Mexico City residents after the deadly September 19 quake found that they nevertheless valued the alerts. The scientists wrote: “[T]here seems to be general acceptance of the technical limitations of the early-warning system in exchange for some measure of peace of mind, for fostering the general awareness of earthquake hazards, and for promoting protective behaviors such as evacuation from buildings that may be prone to collapse.”

Last fall, the USGS’s ShakeAlert started testing alerts to commercial and institutional users in California, such as Northridge Hospital Medical Center and BART. The USGS program spans California, Oregon, and Washington, but the Pacific Northwest still lacks public quake alerts, despite the threat posed by the infamous “Really Big One”—aka a “full-margin rupture of the Cascadia subduction zone”—that seismologists warn could devastate the Seattle region in coming years.

Asked when an alert system might begin in Washington, Maximilian Dixon, who manages earthquake programs for the Washington Emergency Management Division, told Seattle TV station KIRO 7 in November: “I would like to shoot for the end of 2020, that would be fantastic … It would be great if we could do it tomorrow.”