New weapons in the fight against emerging biothreats

In the midst of the Ebola outbreak, progress is being made on other fronts against bacterial threats such as anthrax and MRSA.

As U.S. and international scientists scramble to develop a vaccine to stem the Ebola outbreak, federal researchers armed with powerful developmental and computational systems and resources have figured out how to kill deadly bacterial threats such as anthrax.

The Department of Health and Human Services' Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response said Oct. 16 that its Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority had signed a one-year, $5.8 million contract with Profectus BioSciences. It is the third vaccine development agreement in the federal government's pipeline. All the vaccines will take months to develop and test before they can be used in the field.

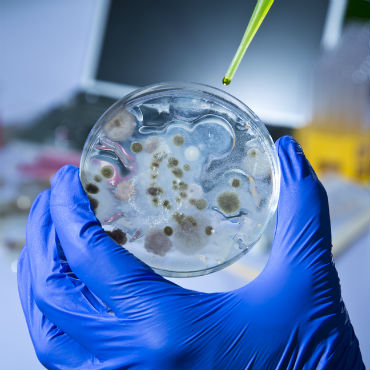

Meanwhile, researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory said they have found a method of killing bacterial organisms, one of which has been linked to past biological attacks in the United States. In a statement released Oct. 3, lab officials said scientists have developed antibiotics that kill bacteriological "superbugs" that have become resistant to antibiotics, such as anthrax and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

LLNL researchers were issued a patent in September for producing antimicrobial compounds that degrade and destroy antibiotic-resistant bacteria by using use the pathogen's own genes against it. They said the compounds are also effective against antibiotic-resistant E. coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter and many others. Those infections are more common in the United States than the Ebola virus and have been of increasing concern to hospitals and, in the case of anthrax, to the Department of Homeland Security.

Citing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, the lab said bacterial superbugs infect almost 2 million people and kill almost 23,000 annually.

LLNL researchers discovered a way to turn a bacterium's lytic proteins against itself. Lytic proteins are enzymes that normally produce nicks in cell walls that allow cells to divide and multiply. But used in high concentrations, the enzymes cause rapid cell-wall degradation and cell rupture, a process known as lysis. Lytic proteins circumvent any defenses bacteria have developed against current broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Researchers used genetic sequencing tools to identify which genes inside a bacterium are vulnerable to proteins that can be used to kill it. In tests underway at CDC, the LLNL-developed proteins have killed 100 percent of bacillus anthracis cells, the bacterium that causes anthrax.

LLNL said its gene-sequencing resources, developed under its long-running participation in the Human Genome Project and other initiatives, allowed its team to shorten the length of time required to sequence bacterial genomes to a few weeks to get information on new pathogens, unknown bacteria species and even species yet to be sequenced.

NEXT STORY: The FBI Wants Internet Wiretapping Powers