What to Know About the Drug-Resistant Superbugs That Killed 23,000 Last Year

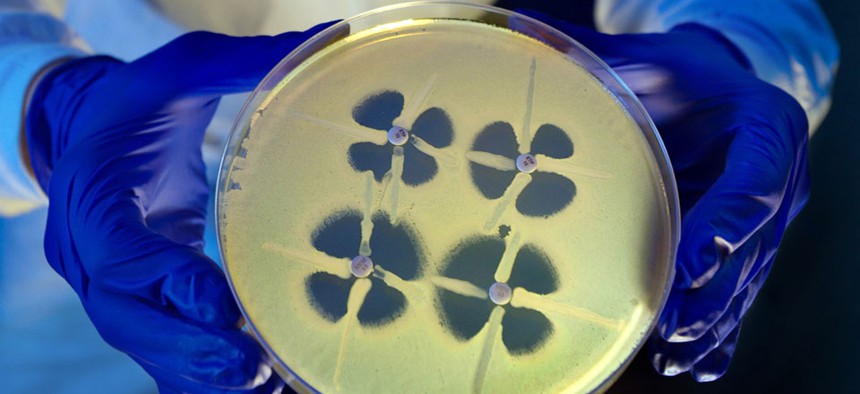

A CDC scientist holds up a petri dish during an experiment involving Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

A Q&A with a CDC scientist.

We created the nightmare bacteria.

It wasn't on purpose. We could not have invented antibiotics without spurring bacterial evolution. As long as there were some bugs out there immune to the drugs, the population would adapt. Just a few years after antibiotics came into mass use in the 1940s, scientists began to observe resistance. Then, as microbiologist Kenneth Todar writes, "Over the years, and continuing into the present, almost every known bacterial pathogen has developed resistance to one or more antibiotics in clinical use." And now, some bugs are resistant to just about everything.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, known as CRE or the "nightmare bacteria," was not known before 2001. Now, 4.6 percent of hospitals in the United States reported at least one infection in 2012. That number was 1.2 percent in 2001.

CRE outbreaks are the stuff of zombie movies, because no drug exists to fight them. In 2011, at a National Institutes of Health hospital no less, an outbreak of a CRE variant killed six people. CRE germs kill about half the people they infect, but here's the scarier part: "CRE have the potential to move from their current niche among health care–exposed patients into the community," the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports.

Drug-resistant pathogens such as CRE are mainly found in the hospital setting, but they are also found in the environment. A Columbia University study found drug-resistant germs to be "widespread" in the Hudson River in New York, with the researchers suspecting the source was untreated sewage. The more commonly knownMRSA, confined to infections in hospitals in the first two decades after it was discovered, can now be contracted from everyday surfaces such as gym mats.

Last week, CDC released the first comprehensive review of the number of drug-resistant infections and deaths in the country. It's the first of its kind, compiling data from dozens of different strains of bacteria in one report. It finds that at least 2 million Americans become infected with drug-resistant bacteria every year, resulting in 23,000 deaths. The report stresses that these numbers are conservative, as they only take into account infections in acute-care hospitals, not long-term centers.

Recently, I spoke with Jean Patel, one of the authors of the report and a deputy director of CDC's Antimicrobial Resistance Division. She spoke about the need to increase awareness of antibiotic resistance and ways to combat its spread. Her responses have been lightly edited. My questions have been rephrased to sound slightly smarter.

Are we approaching a future where antibiotics will be obsolete?

Antibiotics are always going to have a role, but what we have to decide is to stop relying on them as the only role. So now we have to think, and have a greater focus on prevention of the transmission of resistant pathogens and using antibiotics as wisely as possible.

There are some infections like strep throat where antibiotics are going to be needed. But there are other infections, like upper respiratory tract infections, the common cold, where antibiotics are not necessary. And your doctor can help guide you through that choice. I think it is important on both sides—the doctor and the patient—to decide that antibiotics aren't always necessary.

Any threat of—or just a hypothetical threat—of a drug-resistant pandemic?

I think the scary endpoint that we are looking at are bacteria that are becoming resistant to all agents that could be used for treating them. Right now we have some of those pathogens, but they may be limited to certain populations. An example is CRE. Right now, those are bacteria that are becoming resistant to nearly every drug. But right now they are only causing infections in the health care setting. We anticipate that changing. We saw that happen with the ESPL producing Enterobacteriaceae, but it hasn't happened yet. But we think we have some time before it does happen. But we need to beef up our focus on prevention.

What does prevention look like? And what role does pharmaceutical innovation play?

I think it needs both. On one end, we need health care providers to make better decisions about using antibiotics. And I think to do that we need more information. We need to get more information in the hands of those health care providers so they can make the best decisions possible.

And we're working on expanding the scope of our ability to track antibiotic resistance and also antibiotic use in health care settings. So a physician would look at the antibiotic use and in their health care setting they'd be able to benchmark what's happening in their setting, and compare to other health care settings.

The report calls for an end of antibiotics use in livestock. How might that happen?

Antibiotics need to be used in the process of food-producing animals. But we are asking that this be used to manage infections and not be used to promote growth of the animals. And this is consistent with what the Food and Drung Administration has proposed. So the FDA has draft guidance that maps out a plan for phasing out antibiotic use for growth promotion in animals, and instead using these antibiotics to manage infections in animals. And we support that.

What's the take-home lesson?

The most important thing for the patients is a focus on antibiotic use. Having that conversation with your physician about whether antibiotics are really needed for the illness that they have.

Do we have numbers on antibiotics misuse?

In the health care system, we estimate that 50 percent of antibiotic use is unnecessary or not appropriate.

Can we ever stop the creation of new drug-resistant germs?

We can slow it down. Nature will take its course wherever antibiotics are used. Resistance will emerge, but we can slow that.

NEXT STORY: Obamacare on track despite IT hiccups