sponsor content What's this?

Feds Prepare for Cyberattacks — and What Happens After

Presented by

FedTech

Cyberthreats are inevitable, and agencies want to have a comprehensive plan of attack for the days and hours after.

Train users to spot anomalies. Invest in technologies that keep intruders out.

But what happens after defenses fail?

Today, agencies want to invest in technologies that help their leaders respond in the hours and days that follow an intrusion.

“People need to do the basic blocking and tackling, the cyberhygiene, that’s part of the normal course of operating a network,” says John Felker, the director of the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC), a division of the Department of Homeland Security. But agency leaders should take responsibility for the next step. “What are the things you need to do in case you do have a bad day?”

Felker would know. He’s seen his share of bad days as the NCCIC coordinates the national response to significant cyberevents and shares information about cyberthreats with international allies. But by properly preparing for these incidents, Felker says, agencies can mitigate the damage from a successful attack and gather the information necessary to assist with an investigation. In particular, he points to technologies such as network visibility, network segmentation and asset management as the best ways to help agencies respond to hacks.

“Leadership needs to own the problem,” Felker says. “They don’t need to know the ones and zeroes, but they have to view this as part of their responsibility.”

Sean Pike, program vice president for security products at analyst research group IDC, says a response plan is great, but no foolproof manual exists for every situation.

In short, “attacks vary,” he says.

Limit the Damage After Cyberattacks

As cyberthreats become more sophisticated, many feds have resigned themselves to the fact that their efforts are doomed to fail occasionally.

“Organizations are taking a more pragmatic approach, thinking that attacks and intrusion are not a matter of if, but when,” says Andrew Krug, CISO for the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Photo credit: Jimell Greene

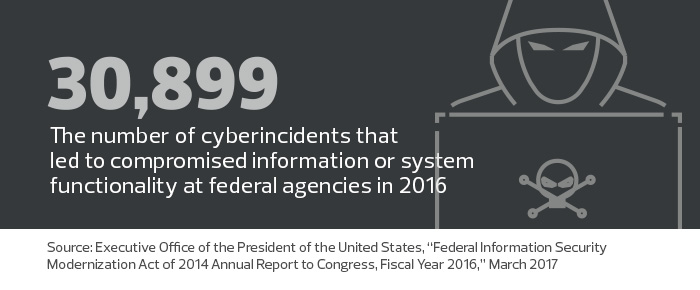

The question becomes not whether hackers will eventually gain access to an agency’s network, but how much damage they’ll do once inside. According to the Ponemon Institute, the average consolidated cost of a data breach in 2016 was $4 million. For government agencies that handle sensitive data — a critical component of citizens’ privacy and national security —the information is priceless.

The game for IT managers then becomes how to leave the intruder few options, like a mouse trapped beneath a shoebox.

Krug calls network segmentation “the building block” necessary to limit the damage that hackers can wreak once they penetrate a network. “It’s profoundly easier to respond to an attack if you know that an attacker will be constrained to the four walls of a particular boundary or network segment,” he says.

Felker agrees. “The first thing that adversary is going to try to do is move laterally within the network, and of course, the holy grail is to get root access,” he says. While smart network architecture can help prevent this sort of movement, Felker notes strong credential management is also essential. If privileged users rely on the same ID and password both for routine business and to access sensitive systems, for example, hackers may be able to gain broad access through a simple phishing attack.

“That’s just not good practice,” Felker says.

Containing threats at the device level is also crucial. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) implemented Cisco Advanced Malware Protection, which automatically quarantines an infected file or machine during an attack.

“It’s a powerful tool,” says Mittal Desai, the agency’s chief information security officer.

Enable IT Security Teams to Respond Rapidly

IT managers have learned to follow the adage: You can’t fight what you can’t see.

Technologies that detect anomalies early on and processes that alert administrators to problems are vital. In particular, a high level of network visibility will help agencies not only spot problems and respond to them, but also figure out where the attacks originated. This often entails shining a light into “the deepest, darkest corners of their networks,” Krug says.

“When you’re processing so much data and so many events, it’s really important that you’re able to establish the necessary protocols to automatically determine what’s bad and what’s good,” he says. “Otherwise, you just have a bunch of noise.”

Network visibility is only part of this equation but can quickly become a near Sisyphean task for big agencies that add new devices to their operations nearly every hour.

“If you don’t have any idea where things are, and how the network is structured, then you’re going to be at a loss when you try to mitigate adversaries, which gives them a whole lot more time to operate,” Felker says.

Plan and Prepare for Coming Attacks

At FERC, IT staff started holding tabletop cybersecurity exercises, a type of low-impact war game, to work through simulated attacks and to identify weaknesses in response plans, Desai says.

“In the past, we didn’t do enough of this, and I think that caused some miscommunications,” he says. “When an incident occurred, the left hand wasn’t talking to the right hand.”

Felker recommends agencies further their relationship with DHS to ensure their incident response plans are as effective as possible. While some agencies are required to work with NCCIC, most IT leaders voluntarily choose to ask the center for help.

“Our objective is not to put people on report,” Felker says. “Our objective is to help you protect your network more effectively. If you’ve established a regular working relationship with us, when something happens, we’re going to understand you better, you’re going to understand us, and we’ll get to a more effective resolution.”

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR CYBERSECURITY INCIDENT RESPONSE

In a June 2016 presidential policy directive, the White House laid out five principles to guide government’s response to cyberincidents. They include:

Shared Responsibility: Individuals, private companies and the government all have a shared interest in — and responsibility for — protecting the country from cyberattacks.

Risk-Based Response: Actions and the resources needed are based on the risks posed to an entity, national security, foreign relations, the domestic economy, civil liberties, and public health and safety.

Respect for Affected Entities: Government responders will safeguard privacy and civil liberties.

Unity of Effort: Agencies that become aware of cyberincidents will rapidly notify relevant agencies to help develop a unified response.

Restoration and Recovery: In response to an incident, government activities will lead to the restoration and recovery of an entity that has experienced an event. These activities will include balancing investigative and national security concerns with the need to return to normal operations.

This content is made possible by FedTech. The editorial staff of Nextgov was not involved in its preparation.