Pictures from the stars, powered by cloud

NASA's Pluto flyby beamed never-before-seen images to audiences new and old. Cloud services helped make the event go smoothly.

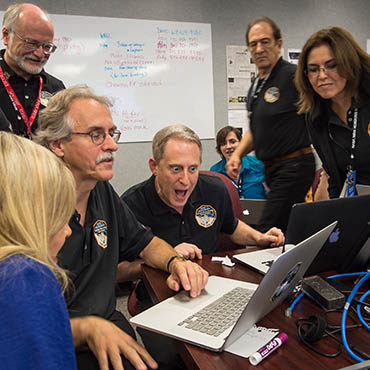

New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern of Southwest Research Institute, center, along with other team members, reacts as he views new images from the spacecraft for the first time at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md. (Bill Ingalls / NASA Flickr)

When the New Horizons spacecraft zipped past Pluto at 7:49 a.m. EDT on July 14, hundreds of thousands of people were watching.

Cloud underpinnings helped ensure they got the whole picture.

The Pluto flyby was a “true success story,” said Raj Ananthanpillai, CEO of NASA’s cloud broker, InfoZen.

Between July 13 and 15, NASA.gov racked up 18.5 million page views – 14 percent of a normal year’s traffic in just 3 days – while NASA TV streaming plays hit 783,000, Ananthanpillai told FCW.

Brian Dunbar, Internet service manager at NASA, noted the diverse range of services NASA used to share Pluto images and information: streaming through Ustream as well as the Akamai-powered NASA TV, images via Instagram and Twitter and high-resolution shots through NASA’s own websites.

There was “some trouble with the streaming” on Akamai’s end (it was Akamai’s first live streaming event), Dunbar noted, and a bit of “human error” at NASA (purging an application cache at the wrong time) delayed image publication.

And yet, despite the setbacks, millions worldwide shared the moment of seeing Pluto up close for the first time.

“It would have been much, much different [if this event had been presented back in 2002],” Dunbar said. “People would’ve gotten blank screens.”

Only 43 percent of those watching the flyby did so inside the U.S., Ananthanpillai said, demonstrating the global appeal of the Pluto mission.

On average, he said, NASA events have a 75 percent American audience.

Dunbar noted that NASA is still working out the balance between social media outreach and its own websites – and he said the former will likely never replace the latter.

Social media is attracting whole new audiences, Dunbar said, while the number of people who use NASA sites to get the high-resolution images or deeper technical backstories that social media can’t provide has held steady over the past decade.

The “readily scalable” cloud environment that InfoZen supports via Amazon Web Services, then, will remain a critical base for NASA in years to come, Dunbar said.

It’s not a brand-new thing.

Dunbar noted the current NASA cloud setup is a “natural progression” from work started in the early 2000s – before the term “cloud” had really taken off – as the agency moved to buy space, not physical servers.

For Ananthanpillai and InfoZen, the challenge started in February 2013, when InfoZen took over NASA’s cloud and website support. Looking to switch NASA sites to Drupal and migrate to AWS, InfoZen grappled with a “how to change the tires on a moving car” problem, Ananthanpillai said.

“It’s not rocket science, so to speak,” Ananthanpillai joked. DevOps and a disciplined approach made the work possible, he said.

Shortly before the New Horizons flyby, InfoZen rolled out a NASA.gov redesign, which folded in the seamless content delivery of “infinite scroll,” cleaned up visual clutter and highlighted NASA TV. Ananthanpillai said the new site withstood the user spike the flyby sent its way.

He also praised the elastic, on-demand, scalable nature of AWS cloud offerings, and said “the cost savings are enormous.”

“The beauty of this cloud is you have these things on demand,” said Ananthanpillai. “You pay by the drink.”