Do Computers Need Pressure-Sensing Screens?

Apple's new 3D Touch could be revolutionary.

The computer mouse, when it first went mainstream, was awkward to describe but easy to use. “Instead of typing instructions, one points to pictures on the screen by sliding a handheld device called a mouse along the top of the desk next to the computer,” The New York Times wrote in 1983.

The mouse added a layer of depth to the experience of computing, one that married tactile movement and digital action. It’s the perfect example of technology that makes so much sense you forget it’s there while you’re using it: an interface that feels like it’s as much an extension of the person as it is of the machine.

The same might be said of Apple’s 3D Touch, the pressure-sensor system beneath the screen of the iPhone’s latest models, the 6s and 6s Plus. Much of what 3D Touch enables seems natural: Pressing harder on the surface of the phone elicits a difference response than pressing on it more softly. It is, in this way, a throwback to the analog past—like the way pounding on a typewriter’s keys leaves darker letters on the page. With 3D Touch, if you’re drawing on the iPhone’s notepad, pressing harder will produce a bolder line; or if you're playing the Magic Piano app, pressing harder will make a louder note.

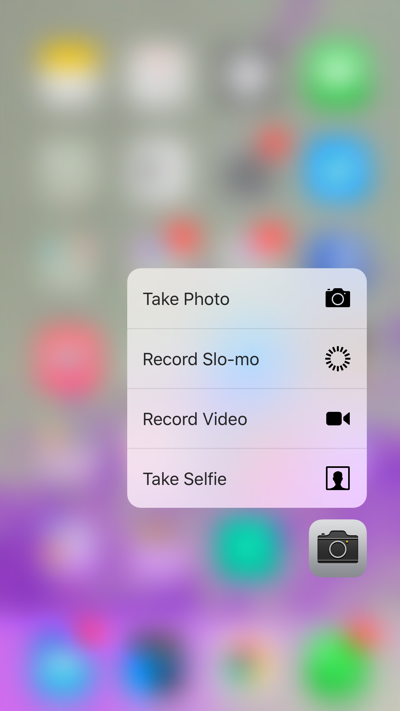

But there are less intuitive applications, too. And it requires some practice to appreciate features like what Apple calls “Quick Actions,” in which pressing harder on some icons produces a list of shortcuts. A hard press on the camera icon, for example, produces a pop-up window that gives you the option to select “take photo,” “record Slo-mo,” “record video,” or “take selfie.” And a hard press on the text-messaging icon produces a list of the three contacts you text most.

When checking email, 3D Touch allows for pop-up previews of messages—so you can glimpse an email without actually opening it. Which maybe sounds like it wouldn’t make much of a difference, from a user-experience perspective. At first, I found it more annoying than helpful. Since then, I’ve found these shortcuts are legitimate time savers once you get the hang of them, but they also represent a significant change to the way people are accustomed to using an iPhone. “I feel like Apple’s demands for ever increasing precision and attention of mobile interface use is exactly the opposite of what I feel capable of giving,” my colleague Ian Bogost told me recently. “3D Touch definitely seems to require a lot of focused practice and attention, and for little reward.”

It’s like what Christina Wodtke wrote for Medium in 2013: “Users don’t hate change. Users hate change that doesn't make their life better, but makes them have to relearn everything they knew.”

It is possible to ignore 3D Touch altogether and use an iPhone 6s like it doesn't have the technology at all. It’s also possible that 3D Touch will become standard, and that the “hard press” will become part of the muscle memory of using a smartphone, the way the original iPhones normalized the swiping and pinching of fingers across tiny screens. Samsung’s Galaxy S7 phone, which is set to be released in March, will have its own pressure-sensitive screen, according to The Wall Street Journal.

So we’re only just beginning to see what pressure-sensitive screens will mean for how people use phones. And a lot of that is because developers are still figuring out what to do with the technology. “Anyone who’s a repeat early adopter of new iPhones shouldn’t be surprised that support for the 6S’s flagship feature [3D Touch] remains scattered close to three months in,” wrote Jacob Kastrenakes forThe Verge. “It was the exact same way at this point when apps had to update for the iPhone 6’s larger screen—it took Starbucks an entire year—and apps lagged behind on adding Touch ID support, too. 3D Touch is going to be even harder.”

For Magic Piano, figuring out what to do with 3D Touch was obvious. “For the original version of Magic Piano on the original iPhone, as soon as you touch your finger on the screen, it registers the touch and it plays the note,” said Yar Woo, the vice president of engineering at Smule, the company that makes Magic Piano. “But for 3D Touch it’s a little different. It’s more of a curve, not a single point of impact.”

3D Touch relies on 96 sensors beneath the phone’s screen. Magic Piano developers ended up introducing a small latency—just enough of a pause after the moment someone touched the screen, to be able to tell whether they’d end up pressing harder. “Just that tiny fraction of a second to know that the user is pressing hard versus pressing soft,” Woo told me. “We delay it 30 milliseconds. You can’t really notice it when you’re actually playing.”

Smule’s co-founder and CEO, Jeffrey Smith, compares the difference between earlier iPhone models and the ones with 3D Touch to a technological leap in music technology. “When you listen to gifted harpsichordists play on the early harpsichord, they were still incredibly expressive because they used time to create emphasis, to elucidate the structure of the music,” Smith said. “That’s basically what we had on the Magic Piano, and that’s all we had: Expression through controlled time … Now we’re able to allow this second dimension of creative expression.” (Though iPhones still aren’t as good as Steinways, he added. “Steinway’s better, but a Steinway doesn’t fit on my train into the city.”)

Endless Reader, an app designed to help kids learn the alphabet and practice reading, uses 3D Touch to change the look and sound of animated letters. Words appear on the screen and kids press individual letters to hear what sounds they make. A harder press has a speeding-up effect, and the sound of a letter is higher pitched. More pressure makes the la-la-la of an L, for example, become increasingly trill and chipmunkish.

“In our experience, the 3D Touch is almost more intuitive to children,” said Joe Ghazal, the chief operating officer of Originator, which makes Endless Reader. “Adults have to be taught a little bit because they have preconceived notions.”

An example to drive home the point: Long before 3D Touch was available, Originator observed kids playing with Endless Reader during app testing, and noticed they often varied the pressure they used when touching the screen as a way to explore what might happen.

Radif Sharafullin, the lead software engineer at Originator, called 3D Touch a significant achievement for Apple, and for computing generally. Working with the technology called to mind, for him, “the first human interaction with the mouse.”

“3D Touch is one of those milestones,” he said. “It made me feel like a magician for a while.”

NEXT STORY: Star Wars’ R2-D2: The Original Mobile Device