This is What Happens When High Schoolers Build Robots

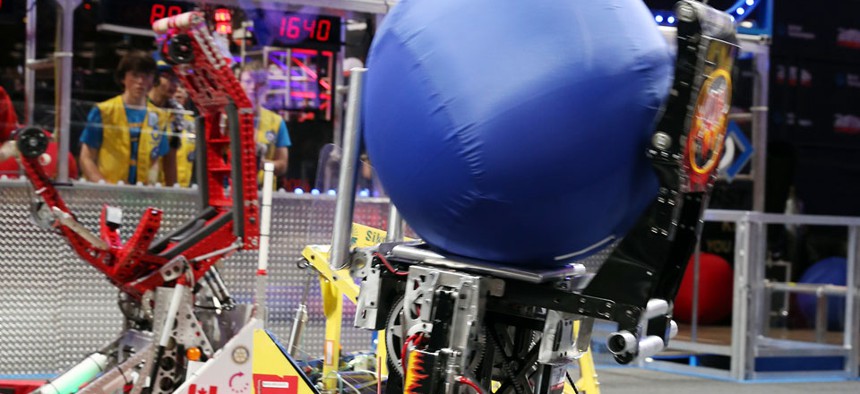

Robots compete at the FIRST robotics competition. Adriana M. Groisman/FRC

A tournament for tech leaders of the future is rooted in traditions of the past.

Sometimes I think of school as an overlapping set of calendars. Students come in and out of eras: testing season, soccer season, marching-band season. Semesters and trimesters overlap and interfere. Everything arcs toward and away from the summer.

This weekend, a considerable season began for thousands of kids across the country and world. The FIRST Robotics Competition, the largest and most famous international robotics competition for high schoolers, announced its new game for 2015. Over the next six weeks, about 75,000 students, working together in 3,000 teams, will devote millions of hours to solving the challenge.

I watched the announcement in a central New Jersey high school, along with 1/75th of those teenagers and teachers. Bedecked in colorful team T-shirts, the thousand of them seemed to well represent the state’s diversity. Facing a giant screen in the middle of the auditorium, they—along with many of the other players across the country and world—watched a livestream announcing the game.

This is the 23rd year of competition for FIRST. The organization—its non-acronymic title is For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology—was founded by MIT professor Woodie Flowers and Segway-inventor Dean Kamen in the late 80s as a reaction against dismal U.S. proficiency in the fields we now call STEM. According to author Neal Bascomb’s 2009 chronicle of a FIRST team, Kamen feared that continued poor performance would turn America into a “banana republic.”

FIRST is now in more than 50 countries, but it was created as an American education intervention aimed at American kids. And what struck me this weekend was how old-fashioned FIRST was. It boasts values that feel straight out of a 1950s science fair. It’s a big high-school sport—the Ultimate Sport For the Mind™— with national championships in a suitably central Midwestern city (St. Louis). The organization prizes Coopertition®—cooperation and competition—and Gracious Professionalism®. (Those are both FIRST’s actual registered trademarks.) And an administrator from NASA even shows up and tells kids how their work has already helped the agency.

Before the livestream started, epic piano-and-synth music played as a 3-D, CGI pattern expanded and collapsed to reveal the logos of some of America’s biggest companies: Google, Dow Chemical, Boeing, Qualcomm, FedEx. The live broadcast was, in fact, referred to universally by FIRST national employees as the live Comcast NBCUniversal Broadcast.

In other words, FIRST hews to midcentury American traditions: sports, space travel, corporate underwriting. And little wonder: Flowers is 71 and Kamen is 63. Both were young men when the U.S. invested in science and engineering education in response to the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik.

Sometimes it feels like a callback to that moment in U.S. history. When the video began, it centered on four white men, all apparently older than 40. They included Flowers and Kamen and a “host”-type, wearing a zipper bike shirt emblazoned with “FIRST”. (Because bike shirts are cool, I guess? But only to dads.) In the video, I saw a diverse set of high schoolers participating in FIRST activities—which matched the diverse collection of students in the auditorium—but the adults were mostly male.

Watching the FIRST video reminded me of my interactions with the national Boy Scouting organization. People, often men, important in their sphere, were telling you things that they considered to be immensely important and discerning—and, with few exceptions, you mostly wanted to get to the fun part.

And the fun part was eventually gotten to. In 2015, the more than 3,000 teams of FIRST will compete in a game called Recycle Rush. It requires robots to stack two different colors of plastic boxes and then place pool noodles inside them. Unlike in previous years, when robots would play often-bruising defense on each other, this year’s game places robots on opposite side of the field, separated by a barrier they can’t cross. On Chief Delphi, the main online forum for FIRST’s competitors, users wondered if the tame nature of the game was in response to FIRST frustration at “violent gameplay.”