Scientists Found a Way to Save a Long-Lost Spacecraft—Now It's Facing Its Biggest Test Yet

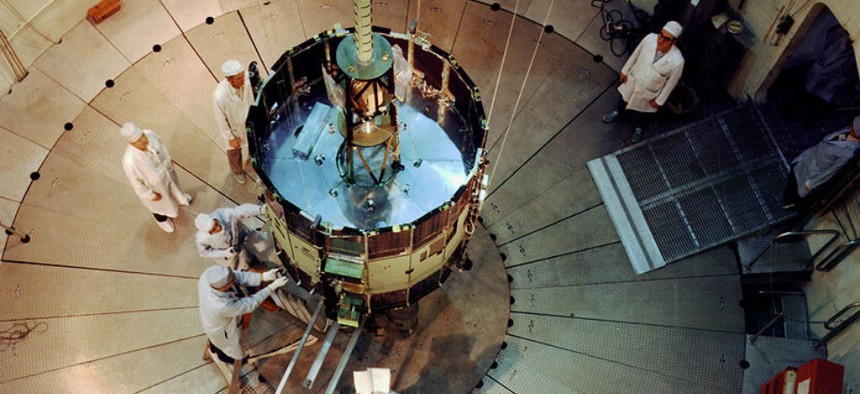

The ISEE-3, undergoing testing and evaluation. Wikimedia Commons

The craft's celestial gauntlet includes a possible collision with the moon.

On April 7, 1986, NASA scientist Bob Farquhar sent final instructions to the International Comet Explorer (ICE), a half-ton probe that had made its way 54 million miles from Earth. It had passed through the tail of Halley’s Comet only a few days before, and now the mission’s flight director told the satellite to go on a long journey. ICE would fall into an Earth-like orbit around the sun, tour empty space, and eventually catch up to Earth in 2014.

Launched in 1978 as a solar observatory, the probe had already spent years in space, hopping from one mission to another. Farquhar imagined future astronauts picking up the satellite as it re-approached its home world. NASA even preemptively donated the craft to the Smithsonian.

“We are now targeted for the moon, but it’s a long time away,” Farquhar told a newswire reporter in 1986. “I’m not going to be able to wait around.” The reporter added that the probe should go “whipping around the moon” on August 10, 2014.

The years have passed, the day is almost here, and only one of Farquhar’s predictions came true: He did wait around, and now he is helping to revive ISEE-3.

He’s doing it in lieu of NASA, which ended transmissions with the craft in 1998 and threw out its documentation. A group of unaffiliated scientists, engineers, and fans have revived the satellite themselves , relying on donated radio-telescopes and their own archival work to figure out how the probe works.

Days ago, in a move that many people doubted was even possible, they made two-way contact with the almost-36-year-old spacecraft, and they’ve declared themselves “in control” of it as it rapidly approaches its home. The moment is undeniably cool: Using old-fashioned archival sleuth work, citizen scientists hack their way into an abandoned space object. The team, led by journalist Keith Cowing and space engineer Dennis Wingo, hope to make almost all the data from the ISEE-3 public, and to create a scientific community around the decades-old probe.

But the latest chapter in the life of the probe—usually referred to by its original name, the International Sun/Earth Explorer-3 (or ISEE-3)—is just beginning. Now that the reboot mission is in control, they must successfully navigate the craft around space hazards before they can normalize its operation. Once they figure out how to stabilize the probe, they'll focus on what they want to do with it.

Now that the reboot mission is in control of the ISEE-3, here’s what they must do to keep it alive.

A Fast-Rising Graph

By June 17, the reboot team needs to fire the probe’s rockets.

Engineers talk about the fuel available to spacecraft in terms of “ delta-v ,” or the amount of energy that needs to be expended for a spacecraft to change velocity. The team believes that ISEE-3 has about 150 meters per second of delta-v remaining: The probe can change its velocity a net 150 meters per second before it runs out of hydrazine to shoot out of its small jets.

As the ISEE-3 gets closer to the Earth and moon—and the two orbs’ gravitational pull strengthens—it will need more and more energy to change its orbital trajectory. The same amount of delta-v lets the spacecraft change its orbit less and less.

When I talked to Cowing, one of the directors of the reboot mission, he said that the graph that describes how much fuel the ISEE-3 would need to change direction resembles a world-population graph. There’s a long, slow upward increase followed by a huge up-swing (which, for world population, comes after the Industrial Revolution).

That inflection point—the moment when it takes huge amounts of fuel to make any tiny movement at all—arrives on June 17. After June 17, in other words, it will be hard to adjust the probe’s trajectory at all. And the ISEE-3 scientists still need to figure out how to tell the probe what to do, a task that—if possible—will require lots of tedious work. You can’t program a flight path into the ISEE-3 because it has no computer.

“Someone literally has to sit there and hit return for a period of time,” Cowing said, and tell the craft to have its tiny rockets fire “itty-bitty pulses.”

A Moonshot

August 10 might be the last day of the ISEE-3’s life. That’s the day it will make its lunar pass, and the ISEE-3 reboot team will gather at McMoons, an abandoned McDonald’s on the grounds of NASA’s Ames Research Center , to watch. (Many of the members of the ISEE-3 reboot team first worked together as part of the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project , which digitized the film of five lunar orbiters from 1966 and 1967.)

According to Farquhar’s original programmed orbit, ISEE-3 will pass about 50 miles over the surface of the moon on August 10. The probe’s not quite where it was programmed to be, though, and—without changes to its trajectory—it might crash into the moon.

“The odds of it hitting the moon are not that great, but they’re not zero,” said Cowling. There’s also a possibility that the half-ton craft could veer toward Earth. Only fine adjustments to ISEE-3’s orbit in the next few weeks will make those two unlikely scenarios impossible.

But that pass doesn’t end the craft’s day. After it flies above the lunar surface, the ISEE-3 will swing behind the moon. That will lead to something of a problem. The probe’s battery expired decades ago, so it can now only run on solar power. For the half-hour it spends on the moon’s dark side, the ISEE-3 will be beyond the reach of solar rays. It will lose power.

The ISEE-3 has lost power like this before, but it was years ago. Now with a couple extra decades of possibly frayed or fried circuitry, it’s less clear that the probe will survive the sudden darkness. (Cowler noted that the probe won’t “turn off.” It will instead lose power at once, like a lightbulb in a power outage.)

If the craft neither crashes into the moon nor expires on its dark side, it will have endured August 10 and the most dire threats to its existence.

And Then Where Does It Live?

After this celestial gauntlet, the ISEE-3 will have a calmer couple of months.

“Once you come out from behind the moon, depending on where we are, we’re going to fire the engines a last few times,” said Cowler. The reboot team still hasn’t decided which direction they’ll fire them in. They could possibly pilot ISEE-3 back to where it began its mission in the 1970s: the first Lagrange point , a stable oasis between the Earth and the sun. But two more spacecraft, with more advanced sensors than ISEE-3, already inhabit that point, so it wouldn’t be of enormous scientific utility.

“The problem [with a Lagrange point] is stopping once you get there,” added Dr. David Chenette, director of NASA’s heliophysics divisions. Maintaing a stable orbit in a Lagrange point requires extra fuel to both stop a craft and tailor its location.

“We want to put it somewhere where we don’t have to spend as long tweaking it as we do running it,” Cowler said. The team is considering “a variety” of easy orbits between the Earth and the moon that would require less fuel but still provide interesting, useful data.

He also raised another possibility: “We could also throw it at another comet in 2018.”