The future of cybersecurity could be sitting in an office in New Jersey

SANS Institute

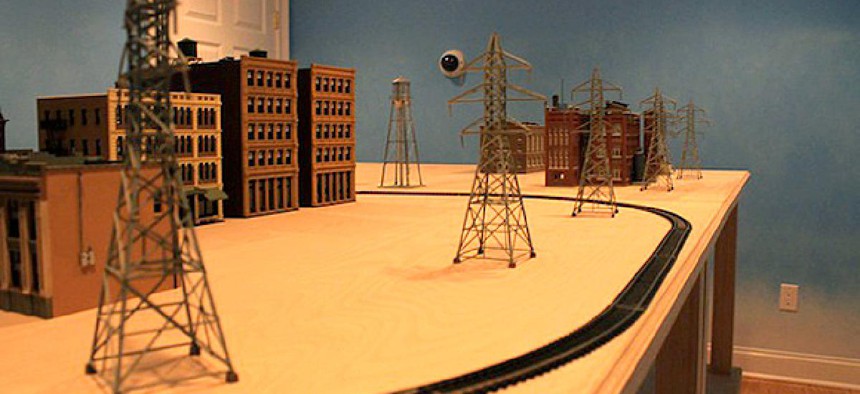

Meet CyberCity, the model train town hoping to keep your home safe from attack.

The Sans Institute was founded in 1989, and currently leads information-security training for military, government, and civilian officials -- sessions that tend to specialize, these days, in digital forensics and network penetration testing. For the past few years, SANS has been running computer simulation training games (the aptly named "NetWars") for members of the military. But those simulations, officials realized, were insufficient to prepare people for the threats we face -- because cybersecurity, its name notwithstanding, doesn't merely concern cyber-environments. Our physical infrastructures -- our streetlights and power grids and airports and hospitals -- are also connected to, and reliant on, computer networks. Which means that, in a predictable yet fairly horrible twist, our cities themselves are vulnerable to cyber attacks.

So SANS, to account for all that, built a new model, this one intended to capture the "kinetic effects" of cyber warfare -- and meant to emphasize the connection between invisible data and physical destruction. And the game that SANS built, CyberCity, is equal parts hilarious and terrifying: a modified model-train town, 6 feet by 8 feet in width, constructed -- hilariously, terrifyingly -- with parts from a local hobby shop. The game that is trying to prepare the powerful for impending cyberwarfare is currently, Fast CoExist reports, "sitting in an office in New Jersey."

Here's Emily Badger, explaining the 21st-century version of a 19th-century amusement:

CyberCity has its own train network, a hospital, a bank, a military complex, and a coffee shop complete with--and this is crucial to the exercise at hand--free Wi-Fi. The town is virtually populated by 15,000 people, each with their own data records and electronic hospital files. Much of the model town literally came from a hobby shop, but the technology and systems that make it run are modeled on the real world. The power grid components, for example, are the same ones you'd find in an actual city.

NEXT STORY: Obama picks counterterrorism adviser to head CIA