What an NFL Coach, the Pentagon and Election Systems Have in Common

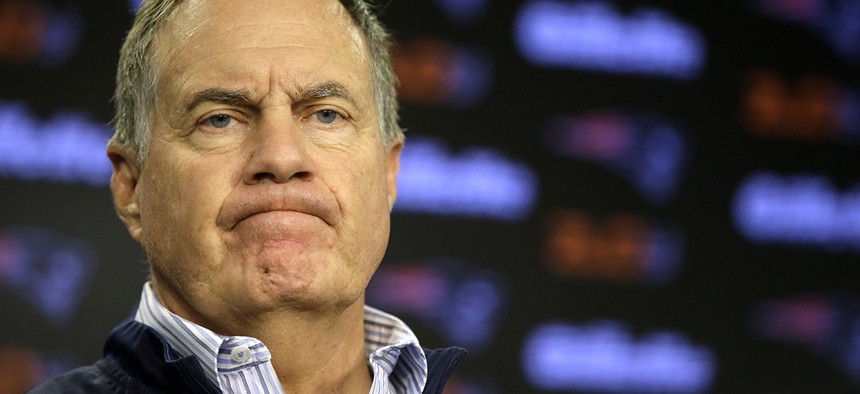

New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick Steven Senne/AP

Does going low-tech make sense in some circumstances?

Sometimes, old-school paper trumps new-school technology.

Bill Belichick, the hoodie-wearing head coach of the New England Patriots, lashed out against the tablets and coach-to-player communications devices his team and others around the National Football League employ with increasing frequency. Cameras caught him smashing a Microsoft Surface tablet on the sideline.

“I'm done with the tablets. I've given them as much time as I can give them, they're just too undependable for me,” Belichick said Tuesday in a conference call with reporters. “I'm going to stick with pictures as several of our other coaches do as well because there just isn't enough consistency in the performance of the tablets, so I just can't take it anymore.”

» Get the best federal technology news and ideas delivered right to your inbox. Sign up here.

The normally tight-lipped Grumpy Cat of a head coach—known for his disdain for revealing even a modicum of information at press conferences—went on to introspectively detail how other tech-related communications, including helmet headsets, “fail on a regular basis.” He detailed several instances where technology failures actually impacted football games.

“Overall, there is a lot of complexity to the technology,” Belichick said. “There is a complexity to multiple systems and there are a lot of failures. I’ve tried to work through the process, but it just doesn’t work for me and that’s because there’s no consistency to it.”

Microsoft went on to issue a statement standing by the reliability of one of its most popular products, but as one of football’s most innovative minds, Belichick’s actions are likely to speak much louder.

And in truth, Belichick’s reversion to the “reliable” old school and rejection of new technology simply for the sake of having it is common. Sometimes, out with the new and in with the old works.

Take, for example, the American election system.

In recent weeks, the election system has come under scrutiny, stoked by fears that the Nov. 8 election could be hacked or rigged. While countries like Estonia allow citizens to vote online, paper still plays a big role in America’s decentralized voting system.

Many precincts across the country still use traditional paper ballots, and 75 percent of votes cast on electronic voting machines (which are not connected to the internet or other voting machines) leave a paper trail. A voting system based on paper doesn’t require an impossibly secure and reliable IT infrastructure.

“Every day, you read about new break-ins and disclosures of information and the vulnerability of our information infrastructure,” MIT professor Ron Rivest recently told Motherboard. “It makes it clear that it’s just a place we shouldn’t want to go to. Voting is too important to put online—we don’t have the tools to make it secure yet. Someday, we may, but it’s not in the near term.”

The election system has good company in being old yet impressively reliable.

For decades, the U.S. nuclear arsenal has operated on hardware from the 1970s equipped with 8-inch floppy disk drives. In a congressional hearing that called out the oldest IT systems in government, Defense Department Chief Information Officer Terry Halvorsen defended the Strategic Automated Command and Control System as “safe and reliable.” While it is scheduled to be updated by the end of fiscal 2017, the system that handles the most destructive weapons in the U.S. military arsenal was built when bell bottom jeans were en vogue.

This "back-to-the-future" approach happens in software, too.

In 2015, the U.S. Navy’s Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command dropped $9.1 million on Microsoft to continue providing custom security fixes for Windows XP, an operating system first released in 2001. Microsoft stopped supporting XP in 2014, but for SPAWAR and its 100,000 machines that rely on the 15-year-old OS, it works just fine—at least until the agency coughs up money to modernize its systems.

Donna Seymour, who served as CIO at the Office of Personnel Management at the time of the massive data breach that compromised the personnel data of 21.5 million security clearance holders, went as far as to suggest before Congress that legacy technology helped the agency avoid a worse hack.

“Most of the government’s data is in a mainframe,” she said before the House in June 2015. “The adversaries in today’s environment are typically used to more modern technologies and so in this case, potentially our antiquated technologies may have helped us a little bit.”

In today’s ubiquitously connected society, reverting to antiquated technology isn’t a silver bullet, but arguably it’s been useful in certain circumstances.

After former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked some of the intelligence community’s surveillance secrets, it was widely reported that Russia’s Federal Guard Service—equivalent to the U.S. Secret Service—bought 20 specialized typewriters. Presumably, it bought some good old-fashioned paper, too.

A U.S. official understands the appeal: The security is so much simpler.

“Personally, and I wouldn’t have a job if this happened, I’d like it if everybody had typewriters and punch cards,” Cord Chase, chief information security officer for OPM, said in early October at an event hosted by Nextgov and Government Executive. “It’s much easier to deal with that and secure it.”